Context

- The Citizenship Amendment Bill (CAB) became law after receiving the President’s assent following a bruising debate in Parliament.

- Since then, Assam has been in the throes of violence with its capital under indefinite curfew, and Army and paramilitary columns rolling across multiple towns.

- The protest has also rocked various colleges and university campuses across the nation along with protests in Delhi. Civil society, students and various political parties have opposed the law on various grounds.

- At least three opposition ruled states Kerala, Punjab and West Bengal have said they will not implement the new citizenship law and legal challenges have been made in the Supreme Court.

What is the Citizenship (Amendment) Act?

- The act is sought to amend the Citizenship Act, 1955 to make Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, and Christian illegal migrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, eligible for citizenship of India.

- In other words, it intends to make it easier for non-Muslim immigrants from India’s three Muslim-majority neighbours to become citizens of India.

- Under The Citizenship Act, 1955, one of the requirements for citizenship by naturalization is that the applicant must have resided in India during the last 12 months, as well as for 11 of the previous 14 years.

- The amendment relaxes the second requirement from 11 years to 6 years as a specific condition for applicants belonging to these six religions, and the aforementioned three countries.

Defining Illegal migrants

- Illegal migrants cannot become Indian citizens in accordance with the present laws.

- Under the Act, an illegal migrant is a foreigner who: (i) enters the country without valid travel documents like a passport and visa, or (ii) enters with valid documents, but stays beyond the permitted time period.

- Illegal migrants may be put in jail or deported under the Foreigners Act, 1946 and The Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920.

- The Bill provides that illegal migrants who fulfil four conditions will not be treated as illegal migrants under the Act. The conditions are:

- they are Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis or Christians;

- they are from Afghanistan, Bangladesh or Pakistan;

- they entered India on or before December 31, 2014;

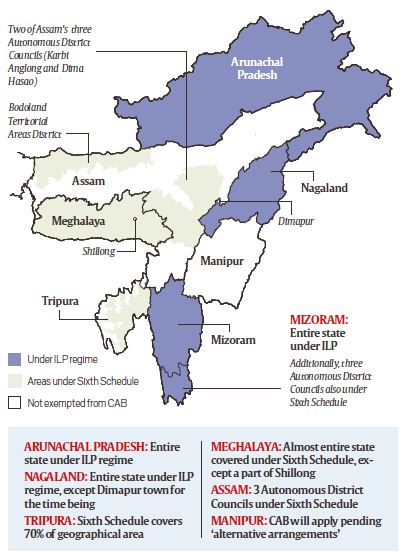

- they are not in certain tribal areas of Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram, or Tripura included in the Sixth Schedule to the Constitution, or areas under the “Inner Line” permit, i.e., Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, and Nagaland.

How many people could now be given Indian citizenship under the new law?

- As of December 31, 2014, the government had identified 2, 89,394 “stateless persons in India”, according to data presented in Parliament by the Home Ministry in 2016.

- The majority were from Bangladesh (1,03,817) and Sri Lanka (1,02,467), followed by Tibet (58,155), Myanmar (12,434), Pakistan (8,799) and Afghanistan (3,469).

- The figures are for stateless persons of all religions. For those who came after December 31, 2014, the regular route of seeking refuge in India will apply.

- If they are regarded as illegal immigrants, they cannot apply for citizenship through naturalization, irrespective of religion.

States exempted from the Act

- Citizenship, aliens and naturalization are subjects listed in List 1 of the Seventh Schedule and fall exclusively under the domain of Parliament.

- Most states of the Northeast are, however, wholly or partially exempted under special provisions for tribal areas, such as Inner Line Permit (Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Mizoram and now extended to Manipur) and the Sixth Schedule with special provisions in practically all of Meghalaya, and a large chunk of Tripura.

Are the communities mentioned indeed persecuted in these three countries?

- The MHA relied on news reports as evidence of religious persecution against minorities in Pakistan, ranging from forced conversion to the demolition of temples and other religious structures.

- Notable examples were Asia Bibi, a Pakistani Christian convicted of blasphemy who spent eight years on death row before being acquitted by the Pakistan Supreme Court.

- In Bangladesh, cases of killings of atheists by Islamic militants are well-documented.

- Although Home Minister referred to non-Muslim religions as persecuted minorities, the law avoids using the word persecution in its text.

Controversy with the Act

- There are two kinds of protests that are taking place across India right now, against the Act. In the northeast, the protest is against the Act’s implementation in their areas.

- Most of them fear that if implemented, the Act will cause a rush of immigrants that may alter their demographic and linguistic uniqueness.

- In the rest of India, like in Kerala, West Bengal and in Delhi, people are protesting against the exclusion of Muslims, alleging it to be against the ethos of the Constitution.

- The fundamental criticism of the Bill has been that it specifically targets Muslims. Critics argue that it is violative of Article 14 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to equality.

I. Country of origin

- The Act classifies migrants based on their country of origin to include only Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

- The statement of objects and reasons states that India has had historic migration of people with Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh, and these countries have a state religion, which has resulted in religious persecution of minority groups.

II. Deviation from its own purpose

- Given that the objective of the Bill is to provide citizenship to migrants escaping from religious persecution, it is not clear why illegal migrants belonging to religious minorities from these countries have been excluded from the Bill.

- India shares a border with Myanmar, which has had a history of persecution of a religious minority, the Rohingya Muslims.

- Sri Lanka has had a history of persecution of a linguistic minority in the country, the Tamil Eelam.

III. Other religious minorities are ignored

- It is unclear why illegal migrants from only six specified religious minorities have been included in the Act.

- For example, over the years, there have been reports of persecution of Ahmadiyya Muslims who are considered non-Muslims in Pakistan have significant population in India.

IV. Date of Entry

- It is also unclear why there is a differential treatment of migrants based on their date of entry into India, i.e., whether they entered India before or after December 31, 2014.

- The logic justifying the date has not been discussed while passing of the said act.

V. Exclusion of Sixth Schedule Areas

- The act excludes illegal migrants residing in areas covered by the Sixth Schedule, that is, notified tribal areas in Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Tripura.

- The act so excludes the Inner Line Permit areas. Inner Line regulates the entry of persons, including Indian citizens, into Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram and Nagaland.

- Once an illegal migrant residing in these areas acquires citizenship, he would be subject to the same restrictions in these areas, as are applicable to other Indian citizens.

- Therefore, it is unclear why the Bill excludes illegal migrants residing in these areas.

Assam Connection

Why is Assam fuming with protests?

- In Assam, what is primarily driving the protests is not who are excluded from the ambit of the new law, but how many are included.

- The protesters are worried about the prospect of the arrival of more migrants, irrespective of religion, in a state whose demography and politics have been defined by migration.

- The Assam Movement (1979-85) was built around migration from Bangladesh which many Assamese see as a threat to their culture and language, besides putting pressure on land resources and job opportunities.

- The protesters’ argument is that the new law violates the Assam Accord of 1985, which sets March 24, 1971, as the cutoff for Indian citizenship.

- If both CAB and the NRC will be implemented, the non-Muslims excluded under the NRC will be included under CAB.

- The net result will be that only Muslims will be identified as illegal migrants and excluded.

- The Assamese fear that Banglaspeakers will easily outnumber Assamese-speaking people in the state, as it has happened in Tripura where Bengali-Hindu immigrants from East Bengal now dominate political power, pushing the original tribals to the margins.

- The Assamese look at the issue from the linguistic, and not any religious angle. For them, Bengalis are one large linguistic community who are growing in numbers and could, one day, become numerically stronger than them.

- Hence, the Assamese view the CAB (Citizenship Amendment Bill) as legislation that will grant citizenship to Bengali-speaking migrants from Bangladesh. And that is something they do not want.

How much of Assam is exempted?

- In Assam, three Autonomous Districts are exempted but the new law remains applicable to the major area.

- This also raises the question: can there be two citizenship laws applicable to the same state?

- Under Clause 5.8 of the Assam Accord, “Foreigners who came to Assam on or after March 25, 1971, shall continue to be detected; deleted and practical steps shall be taken to expel such foreigners.”

Legality and constitutionality check

- Legal experts and Opposition leaders have argued that it violates the letter and spirit of the Constitution.

- One argument made in Parliament is that the law violates Article 14 that guarantees equal protection of laws.

- According to the legal test prescribed by courts, for a law to satisfy the conditions under Article 14, it has to first create a “reasonable class” of subjects that it seeks to govern under the law.

- Second, the legislation has to show a “rational nexus” between the subject and the object it seeks to achieve. Even if the classification is reasonable, any person who falls in that category has to be treated alike.

- If protecting the persecuted minorities is ostensibly the objective of the law, then the exclusions of some countries and using religion as a yardstick may fall foul of the test.

How is this act referred to here?

- Granting citizenship on the grounds of religion is seen to be against the secular nature of the Constitution which has been recognised as part of the basic structure that cannot be altered by Parliament.

- It is argued that persecuted minorities in three neighbouring countries, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan, whose state religion is Islam, is a reasonable classification.

- Another argument is that the law does not account for other categories of migrants who may claim persecution in other countries.

Justification of the Law given by the Central Government

- It is argued that Muslims can never be persecuted in Islamic countries.

- Sri Lanka and Bhutan both Bhutan and Sri Lanka offer constitutional patronage to the state religion, Buddhism.

- Defending the exclusion of Shias and Ahmadiyyas from Pakistan it was argued by the government that a persecuted Shia would rather go to Iran than come to India.

- There are thousands of refugees in India of Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Christians and Parsis who have entered India after facing religious persecution in countries like Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan without any valid document.

- These refugees have been facing difficulty in getting Long Term Visa (LTV) or Citizenship.

- For Naturalization they have to stay at least 12 years in India.

- Those minorities who are persecuted due to their religion have no other place to go except India as the three nations are declared Islamic Nations.

It excludes only “non-Indian” Muslims

- On the face of it, the amendment is not to exclude any Indian citizen. However, the NRC in Assam and the latest citizenship law cannot be decoupled.

- The new law gives a fresh chance to the Bengali Hindus left out to acquire citizenship, whereas the same benefit will not be available to a Muslim left out, who will have to fight a legal battle.

- Plugged with NRC, the new amendment becomes an enabling law to potentially disenfranchise an individual of a religion not mentioned in the amendment.

- Politically, the law is expected to impact West Bengal and Northeastern states. Assam and West Bengal head for polls in 2021.

Conclusion

- India is a constitutional democracy with a basic structure that assures a secure and spacious home for all Indians, including and especially its

- India has to undertake a balancing act here. India’s citizenship provisions are derived from the perception of the country as a secular republic.

- In fact, it is a refutation of the two-nation theory that proposed a Hindu India and a Muslim Pakistan. Granting citizenship based on religious identity violates this principle.

- That being said, we need to balance the civilization duties to protect those who are prosecuted in the neighbourhood.

- Hopefully, the government pays heed to the voices of different communities and takes an action only after a consensus is achieved.

References

https://www.civilsdaily.com/news/explained-nehru-liaquat-agreement-of-1950/

https://www.civilsdaily.com/news/exemption-categories-under-cab/

http://prsindia.org/billtrack/citizenship-amendment-bill-2019