Blamed for leaving their homes in defiance of the lockdown, hungry and cash-strapped migrants are struggling in packed shelters while those who managed to reach their native places are facing hostility. What makes India’s migrant crisis unique is not the nature of its migrant workforce but the abruptness of its public policy.

Context

- Labour migration within India is crucial for economic growth and contributes to improving the socio-economic condition of people.

- Migration can help, for example, to improve income, skill development, and provide greater access to services like healthcare and education.

Labour and migration in India

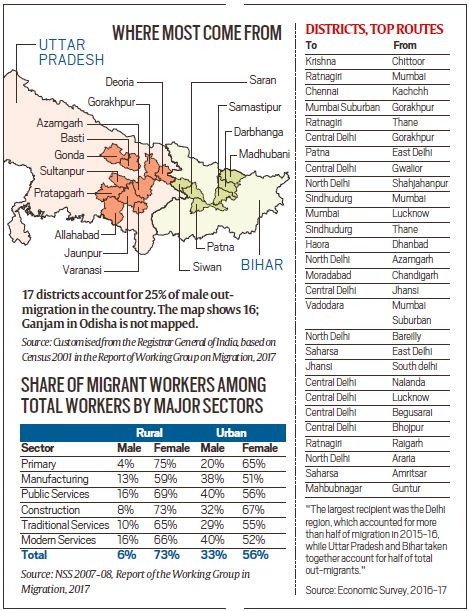

- Seasonal migration for work is a pervasive reality in rural India.

- The annual net flows amount to about 1 per cent of the working age population.

- As per Census 2011, the size of the workforce was 48.2 crore people.

- This figure is estimated to have exceeded 50 crore in 2016 — the Economic Survey pegged the size of the migrant workforce at roughly 20 per cent or over 10 crore in 2016.

Uniqueness of labour migration in India

Migrant labour in Indian cities, and the vast majority of workers currently in the news, is marked by three traits:

1) Internal migration

- These migrants come from within India, unlike international migrants who often dominate the study of migration.

2) Informality

- They are low-income workers who are informally employed, meaning they lack formal contracts.

- Many migrant workers perform daily wage labor (such as beldars on construction sites), or are self-employed (for example street vendors).

- Such employment is obviously precarious and day-to-day in nature, with no protections in the event of an abrupt cancellation, as has happened with the lockdown.

3) Circularity

- Most of these migrants do not permanently relocate to the city. Expensive and inhospitable urban environments compel them to move without their families.

- Instead, they circulate between city and village several times a year and remain deeply rooted within sending villages.

4) Gendered migration

- Women constitute an overwhelming section of migrants. Female migrants are less represented in regular jobs and more likely to be self-employed than non-migrant women.

- Domestic work has emerged as an important occupation for migrant women and girls.

- A gender perspective on migration is imperative since women have significantly different migration motivations, patterns, options and obstacles from men.

Each of these factors is important in understanding why migrant workers have been so eager to return home since the lockdown was announced.

What is their contribution to the Indian economy?

- More fine-grained studies have revealed circular migrants are influential, and in some cases, the predominant forms of labour in industries ranging from construction, brick manufacturing, mining and quarrying, hotels and restaurants, and street vending.

- Many of these sectors are integral to the Indian economy and comprise a significant share of our national GDP.

Has it been recorded and acknowledged properly and accurately?

- The informal nature of employment makes it hard to collect reliable data even on the size of this population, let alone its economic contributions.

- We can gain a sense of these contributions by considering sectors in which employment is dominated by circular migrants.

- Circular urban migrants perform essential labour and provide services that many people want but are unwilling to provide themselves.

- Yet too often this work is not received with gratitude by municipal authorities or more privileged urbanites.

Mass exodus of migrant labour

- The exodus of migrant workers is far from surprising as it was caused by a rational panic triggered by misinformation.

- They live in inhospitable conditions such as cramped rented rooms or are compelled to sleep on the footpath, lack documents to access benefits such as rations in the city, do not have family members in the city, and have few savings to draw upon.

- The lockdown took away their only reason for enduring such hardships: work in the city.

- Moreover, given the nature of the novel coronavirus, it would be completely plausible for migrants to be unsure about when work opportunities might actually resume in cities.

Was it preventable?

- Considering the severity of coronavirus breakdown, an immediate lockdown was inevitable. And the already vulnerable migrants were the first to get impacted.

- However, a more effective and humane response would have first considered how an abrupt lockdown might affect transient populations.

- Given the lockdown order required everyone to stay at home for a prolonged period, it is especially important to consider those populations who are often forced to work far away from their homes.

- Second, a more effective response would have decided whether to prioritize keeping migrants in place in destination cities, or helping them safely reach home.

Threats to covid returnees

- Authorities tend to view migrants through the lens of enforcement rather than accommodation. Circular migrants experience considerable police repression in the cities they work within.

- This attitude remains apparent in the reports and images of police violence towards migrants during this current crisis, and the language of enforcement that pervades recent government orders.

- Clearly the pandemic has produced certain specific responses, such as disturbing images of migrants being rounded up and sprayed with harmful chemicals.

- Yet these responses are hardly divorced from longstanding patterns of marginalization.

- If anything fears stoked by a viral pandemic is especially amenable to being channelled through longstanding systems of classification, purity, and stigma based on caste, class, and occupation.

What could have been done?

- If the goal was to get migrants safely home, resources should be targeted to ensure safe and clean passage and a feasible local quarantine strategy for migrants in their home regions.

- Resources should be mobilized keeping them healthy, housed, and fed (including by enabling them to pay our pause rent, and access PDS benefits in cities).

Issues with migrant’s welfare

1) Lack of reliable data

- We lack a consensus estimate of the size of our circular migrant population for a number of reasons.

- Many official data sources use definitions of migration that fail to capture the transient and itinerant patterns observed by circular migrants.

- For example NSSO collected specific data on migration in its 64th round, and found the all-India rate of ‘short-term migration’ is between 1 and 2 percent.

- The NSS defines a ‘short-term’ migrant as one who stays away for up to 6 months during the last year, but many circular migrants spend most of the year working in cities, returning home for festivals, harvests, or to see family.

- Further, the fact that these migrants live and work in informal conditions in cities, and circulate between village and city, make them especially difficult to access through standard residence-based surveys.

2) Lack of Policy Measures

- The striking difference in how we treat international and internal migrants is particularly apparent if we think of wealthy international diaspora such as Indians residing in the United States.

- Diasporas are celebrated for their accomplishments and remittances and feted at events such as the Howdy Modi rally held recently in Houston.

- The power of these groups fueled significant efforts to expand their standing and political rights, including the establishment of new categories of citizenship (such as the Overseas Citizens of India).

- By contrast there are few systematic efforts to celebrate and acknowledge the contributions of poor circular migrants including the recent One Nation One Ration Card Scheme.

3) Other hardships

- Lack of alternate livelihoods and skill development in source areas, locations from where migration originates, are the primary causes of migration from rural areas.

- Migrants repeatedly face harassment and mistreatment by urban employers, middle-class shopkeepers and residents, and local police.

Most of their vulnerabilities are highlighted as under:

- Lack of Awareness: Lack of awareness among migrants about their rights as ‘workers’ and as ‘migrant workers’

- Work harassment: Unscrupulous labour agents who coerce workers and do not pay minimum wages as stipulated by law

- Human trafficking: Many migrants, especially young girls and women, are deceived and trafficked

- Debt traps: Workers who engage in seasonal work, such as in brick kilns or agriculture, are often trapped in a situation of debt and bondage

- Work safety: Poor and unsafe working and living conditions, lack of occupational health and safety

- Sexual harassment: Possibility of violence at the workplace and sexual harassment of women

- Health risks: Greater threat of nutritional diseases, occupational illnesses, communicable diseases, alcoholism

- Exclusion: Exclusion or lack of access to public services and social protection for migrants due to regulatory and/or administrative procedures in destination states

Conclusion

The challenge is that migrants usually form a class of invisible workers. There are different risks in their source and destination areas. Needs of their family members, including infants, children, adolescents and elderly who accompany migrant workers need to be addressed on a priority.

- Economic growth in India today hinges on mobility of labour.

- The contribution of migrant workers to national income is enormous but there is little done in return for their security and well-being.

- There is an imminent need for solutions to transform migration into a more dignified and rewarding opportunity.

- Without this, making growth inclusive or the very least, sustainable, will remain a very distant dream.

Way Forward

- Since internal migration in India is very large, it needs to be given high priority with specific policy interventions.

- Governments and policymakers can play a vital role in ensuring that migrant workers undertake safe migration, have decent working and living conditions in destination areas, are aware of their rights and have access to social security and welfare schemes.

- Suggestions to promote decent life for migrant workers in India include: developing a policy framework that gives priority to migrants, creates linkages between state and central policies on healthcare, education and social security, and facilitating convergence of state and central resources.

Broadly, these series of measures can be summarized as below-

- Establishing institutional mechanisms for inter-state coordination

- Improving enforcement of labour laws

- Adopting a four-pronged approach for better protection of rights of workers that defines the roles and responsibilities of the state, employers, workers/trade unions/civil society organizations and emphasizes the use of social dialogue and collective bargaining for promoting the rights of migrant workers

- Accessing housing, water and sanitation and other urban amenities

- Universal registration of workers on a national platform and developing comprehensive databases

- Strengthening and/or setting up district facilitation centres, migrant information centres and gender resource centres

- Strengthening the role of panchayats and other local authorities in registering workers

- Providing education and health services at the worksites or seasonal hostels

- Providing skills training, in particular for adolescents and young workers

References

http://www.aajeevika.org/labour-and-migration.php

https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/30/india/gallery/india-lockdown-migrant-workers/index.html