If you haven’t read chapter one and two, read them here first, Chapter two

Data which you can quote in exam to buttress your point-

- 975 million individuals now hold an Aadhaar card – over 75% of the population and nearly 95% of the adult population

- Nearly one-third of all states have Aadhar coverage rates greater than 90%; and only in 4 states—Nagaland (48.9), Mizoram (38.0), Meghalaya (2.9) and Assam (2.4)—is penetration less than 50%

- Basic savings account penetration in most states is still relatively low – 46% on average and above 75% in only 2 states (Madhya Pradesh and Chattisgarh).

- only 27% of villages have a bank within 5 km

- The Kenyan BC:population ratio is 1:172. By contrast, India’s average is 1:6630, less than 3% of the Kenyan level

- spatial density of BC’s in India is 17% the Kenyan level

- Mobile penetration-Only in Bihar (54%) and Assam (56%) is penetration lower than 60%

- there are approximately 1.4 million agents or service posts to serve the approximately 1010 million mobile customers in India, a ratio of about 1:720

This contrast of bank account penetration and accessibility v/s mobile penetration suggests that-

- India should take advantage of its deep mobile penetration and agent networks by making greater use of mobile payments technology. Govt response- licensing of payment banks

- Mobiles can not only transfer money quickly and securely, but also improve the quality and convenience of service delivery

- For example, they can inform beneficiaries that food supplies have arrived at the ration shop or fertilizer at the local retail outlet

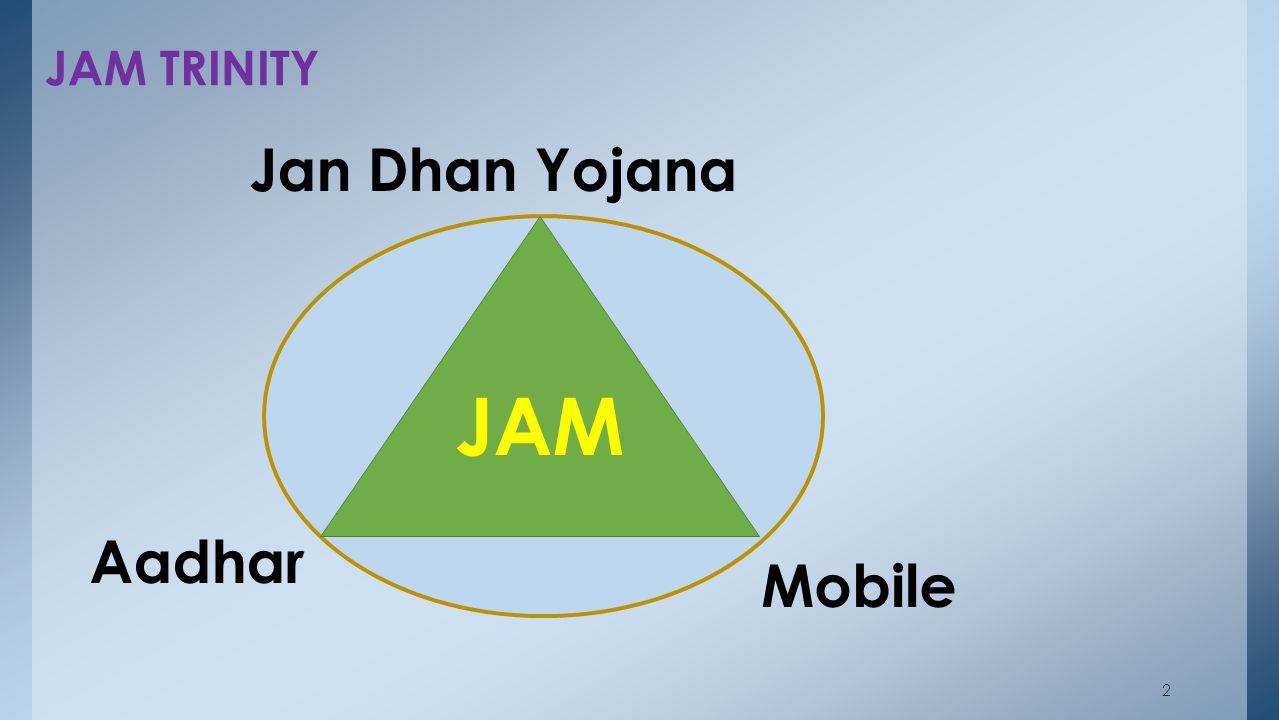

Let’s come to the main issue of Direct Benefit Transfer using JAM-

Suppose the govt wanted to transfer 1000$ to every Indian tomorrow. It would require-

- Ability to identify beneficiaries (Authentication / identification or first mile)

- Ability to transfer money to beneficiaries (bank account )

- Ability to withdraw money from bank accounts (accessibility to bank branches / last mile)

First mile/ identification issues-

- Failure on identification front leads to leakage – benefits intended for the poor flow to rich and “ghost” households, resulting in fiscal loss

- It was due to administrative and political discretion involved in granting identity proofs like BPL cards, driving licenses and voter IDs (not giving BPL card to poor etc)

- Aadhaar uses technology to replace human discretion and can better help in identification

3 Broad issues-

- Targeting – targeted subsidies are harder to JAM than universal programs, as they require government to have detailed information about beneficiaries. For instance- Subsidies targeted at the poor (like food and kerosene) require government to know people’s wealth while a universal subsidy like LPG requires no such information.

- Beneficiary databases: to identify beneficiaries, the government needs a database of eligible individuals in digital form to be seeded with Aadhaar. Socioeconomic caste census (SECC) data needs to be continuously updated to serve as a baseline in sectors where data does not exist.

- Eligibility: household-individual connection, while Aadhaar is an individual identifier, some schemes such as PDS ration are implemented at household level and spending priorities of male and female beneficiaries are often different.

2. Middle mile- administrative challenge of coordinating government actors and the political economy challenge of sharing rents with supply chain interest groups.

- Within-government coordination: among various ministries, departments, state govt., departments etc.

- Supply chain interest groups: distributors need incentives before they invest in JAM infrastructure and if their interests are threatened, they would obstruct the spread of JAM.

3. Last mile/ Transfer and Access issues (Bank account and access)- failure here risks excluding genuine beneficiaries, especially the poor.

- Beneficiary financial inclusion: Bank accounts and accessibility to bank branches.

In rural areas physical connectivity to the banking system remains limited, and BCs, banking correspondents and mobile money providers have not yet solved this last-mile problem

2. Beneficiary vulnerability: amount of subsidy consumed by poor

- exclusion error risks increase when the beneficiary population is poorer

- For instance, the poorest 30% of households consume only 3% subsidized LPG consumption, but 49% of subsidized kerosene i.e. if excluded from LPG subsidy not much effect on poor but exclusion from kerosene subsidy will hurt them the most

Where next to spread JAM?

Policymakers should decide where to apply JAM based on two considerations of-

- Amount of leakages- subsidies with higher leakages will have larger returns from introducing JAM

- Control of the central government-control of central government will reduce administrative challenges of co-ordination and political challenges of opposition by interest groups (middle mile challenge)

Fertilizer subsidies (huge leakages) and within-government transfers (govt control) are two most promising areas for introduction of the JAM

JAM Preparedness Index:

- Aadhaar penetration, basic bank account penetration and Banking Correspondents (BC) density are used as indicators for the indices

- Preparation across states is varied with urban preparation being better than rural one

- In urban areas, Madhya Pradesh and Chattisgarh show preparedness scores of about 70% while Bihar and Maharashtra, have scores of only about 25%

- DBT rural preparedness has an average score of 3% and a maximum of just 5%(Haryana)

It is clear that last-mile financial inclusion is the main constraint to making JAM happen in much of rural India. Jan Dhan’s vision must truly succeed before much of India can JAM

What is this BAPU?

Biometrically Authenticated Physical Uptake

- It is an interim solution– while banking correspondent networks develop and mobile banking spreads

- Beneficiaries verify their identities through scanning their thumbprint on a POS (point of sale) machine while buying the subsidised product—say kerosene at the PDS shop just like your biometric attendance machine

- BAPU preparedness is much better (12%) than for Rural DBT preparedness (3%)

Remarkable success of LPG DBT scheme (PAHAL)

- Use of Aadhaar has made black marketing harder (commercial establishments buying subsidiesd domestic cylinder)

- LPG leakages have reduced by about 24 per cent with limited exclusion of genuine beneficiaries

However, diversion of LPG from domestic to commercial sources continues, because of the differential tax treatment of “commercial” and “domestic” LPG (no tax on domestic unsubsidized cylinders (after 12 cylinders) v/s upto 30% tax on commercial cylinders)

Solution- apply the One Product One Price principle and equalise taxes across end-uses

Way forward on JAM

In those areas where the centre has less control, it should incentivise the states to-invest in first-mile capacity (by improving beneficiary databases),deal with middle-middle challenges (by designing incentives for supply chain interest groups to support DBT) and improve last-mile financial connectivity (by developing the BC and mobile money space). States should be incentivised by sharing fiscal savings from DBT.

- Centre can invest in last-mile financial inclusion via further improving BC networks and promoting the spread of mobile money

- Regulations governing the remuneration of BCs need to be reviewed to ensure that commission rates are sufficient to encourage BCs to remain active

What you have to read for yourself

- All the boxes from the chapter

- Open all the hyperlinks. Learn, understand and revise

- Read this chapter wiping every tear from every eye from last year’s economic survey to understand conceptual framework behind DBT and also follow this story on Direct Benefit Transfer

Ask all your doubts in the comment section below or in doubts clearing forum . all your suggestions, criticism and feedback are most welcome.

If you like what you read, show your support to Civilsdaily and give us a hi 5 at the Android Play – Click here.