Dear Aspirants,

This Spotlight is a part of our Mission Nikaalo Prelims-2023.

You can check the broad timetable of Nikaalo Prelims here

Session Details

YouTube LIVE with Parth sir – 7 PM – Prelims Spotlight Session

Evening 04 PM – Daily Mini Tests

Join our Official telegram channel for Study material and Daily Sessions Here

11th Apr 2023

Let’s begin with the first physiographic division. It consists of:

- THE HIMALAYAS, and

- The Northeastern hills (Purvanchal).

A) The Himalayas:

The Himalayas are the highest and longest of all young fold mountains of the world. The Pamir, known as the roof of the world, connects the Himalayas with the high ranges of Central Asia.

Let’s begin by understanding how the Himalayas came into being:

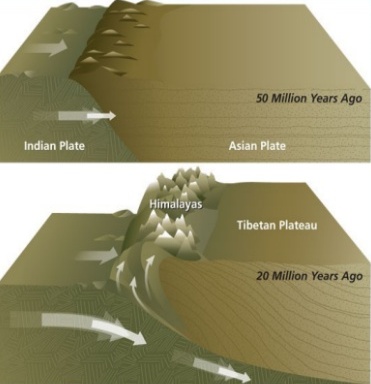

About 40 to 50 million years ago, two large landmasses, India and Eurasia, driven by plate movement, collided. As a result, the sediments accumulated in Tethys Sea (brought by rivers) were compressed, squeezed and series of folds were formed, one behind the other, giving birth to folded mountains of the Himalayas.

Recent studies show that India is still moving northwards at the rate of 5cm/year and crashing into the rest of Asia, thereby constantly increasing the height of Himalayas.

The North-South division of the Himalayas

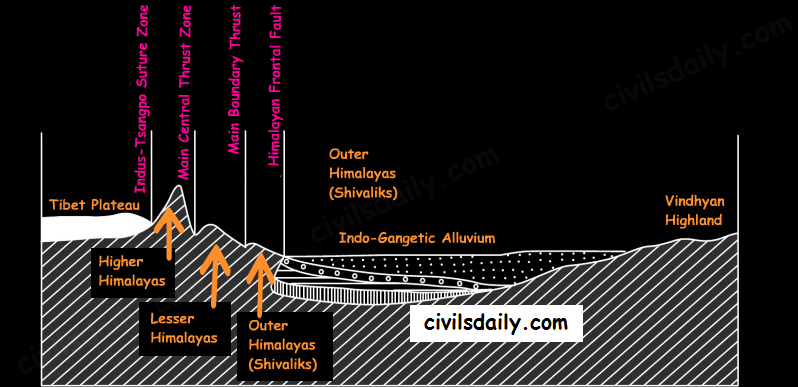

The Himalayas consist of a series of parallel mountain ranges:

- The Greater Himalayan range, which includes:

- The Great Himalayas(Himadri), and

- The Trans-Himalayan range

- The Lesser Himalayas (or Himachal), and

- The Outer Himalayas (or Shiwalik).

- Formation of these ranges: The Himadri and Himachal ranges of the Himalayas have been formed much before the formation of Siwalik range. The rivers rising in the Himadri and Himachal ranges brought gravel, sand and mud along with them, which was deposited in the rapidly shrinking Tethys Sea. In the course of time, the earth movements caused the folding of these relatively fresh deposits of sediments, giving rise to the least consolidated Shiwalik range.

- Characteristic Features:

- Notice in the map shown above that the Himalayas form an arcuate curve which is convex to the south. This curved shape of the Himalayas is attributed to the maximum push offered at the two ends on the Indian peninsula during its northward drift. In the north-west, it was done by Aravalis and in the Northeast by the Assam ranges.

- Syntaxis/ Syntaxial bends: The gently arching ranges of the Himalayan mountains on their Western and Eastern extremities are sharply bent southward in deep Knee-bend flexures that are called syntaxial bends. On both the ends, the great mountains appear to bend around a pivotal point. The western point is situated south of the Pamir where the Karakoram meets the Hindu Kush. A similar sharp, almost hairpin bend occurs on the eastern limit of Arunachal Pradesh where the strike of the mountain changes sharply from the Easterly to Southerly trend. Besides these two major bends, there are a number of minor syntaxial bends in other parts of Himalayas.

Syntaxial Bends of Himalayas

- The Himalayas are wider in the west than in the east. The width varies from 400 km in Kashmir to 150 km in Arunachal Pradesh. The main reason behind this difference is that the compressive force was more in the east than in the west. That is why high mountain peaks like Mount Everest and Kanchenjunga are present in the Eastern Himalayas.

- The ranges are separated by deep valleys creating a highly dissected topography.

- The southern slopes of the Himalayas facing India are steeper and those facing the Tibetan side are generally gentler.

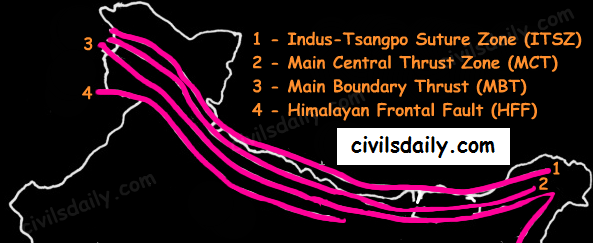

- Let’s take up these Himalayan mountain ranges one by one: The Himalayan Ranges | the Greater Himalayan Range, the Lesser Himalayas, the Shivaliks Indus-Tsangpo Suture Zone: It represents a belt of tectonic compression caused by the underthrusting of the Indian shield/ plate against the Tibetan mass. It marks the boundary between the Indian and Eurasian plates. The suture zone stretches from the North-Western Himalayan syntaxis bordering the Nanga Parbat to the East as far as the Namche Barwa Mountain. The Karakoram Range and the Ladakh plateau lie to the north of ITSZ and originally formed a part of the European plate. Main Central Thrust Zone: This separates the Higher Himalayas in the north from lesser Himalayas in the south. It has played an important role in the tectonic history of these mountains. Main Boundary Thrust: It is a reverse fault of great dimensions which extends all the way from Assam to Punjab and serves to separate the outer Himalayas from the lesser Himalayas.Himalayan Frontal Fault: It is a series of reverse faults that demarcates the boundary of the Shivalik from of the Himalayan province from the alluvial expanse of the Indo-Gangetic plains.

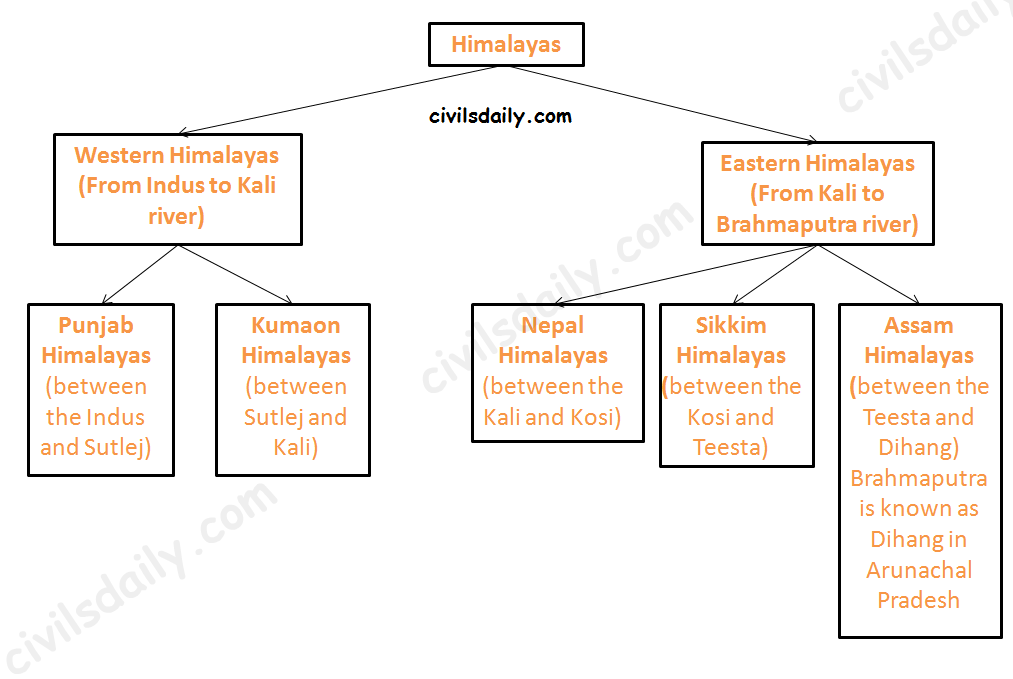

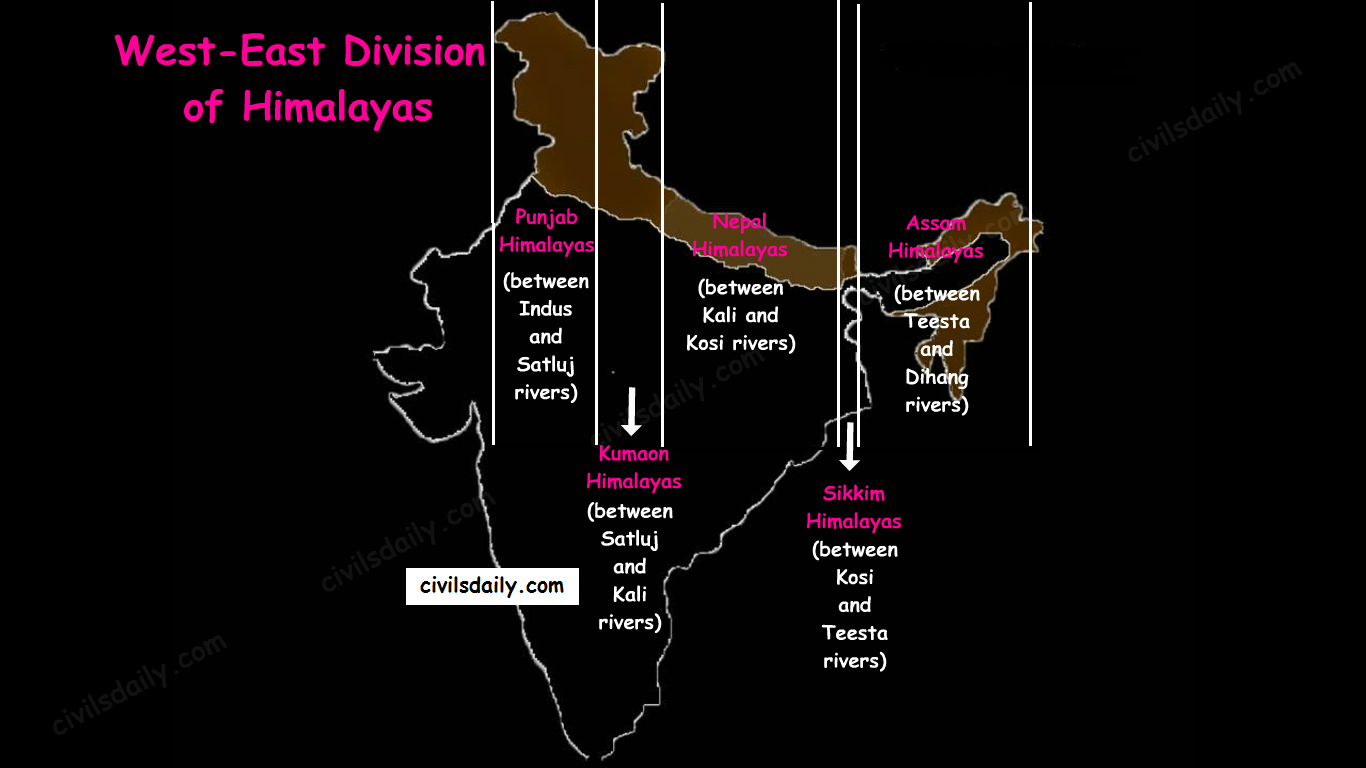

Besides the longitudinal divisions, the Himalayas have been divided on the basis of regions from west to east:

These divisions have been demarcated by river valleys:

- Punjab Himalayas:

- A large portion of Punjab Himalayas is in Jammu and Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh. Hence they are also called the Kashmir and Himachal Himalaya.

- Major ranges: Karakoram, Ladakh, Pir Panjal, Zaskar and Dhaola Dhar.

- The general elevation falls westwards.

- The Kashmir Himalayas are also famous for Karewa formations.

- ‘Karewas’ in Kashmiri language refer to the lake deposits, found in the flat-topped terraces of the Kashmir valley and on the flanks of the Pir Panjal range.

- These deposits consist of clays, silts and sands, these deposits also show evidence of glaciation.

- The occurrence of tilted beds of Karewas at the altitudes of 1500-1800m on the flanks of the Pir Panjal strongly suggests that the Himalayas were in process of uplift as late as Pliocene and Pleistocene (1.8mya to 10kyears ago)

- Karewas are famous for the cultivation of Zafran, a local variety of saffron.

- Kumaon Himalayas

- Nepal Himalayas:

- Tallest section of Himalayas

- Sikkim Himalayas:

- Teesta river originates near Kanchenjunga

- Jelep la pass- tri-junction of India- China-Bhutan

- Assam Himalayas:

- The Himalayas are narrower in this region and Lesser Himalayas lie close to Great Himalayas.

- Peaks: Namcha Barwa, Kula Kangri

- Bengal ‘Duars’

- Diphu pass- tri-junction of India- China-Myanmar

- The Assam Himalayas show a marked dominance of fluvial erosion due to heavy rainfall.

Glaciers and Snowline:

Snowline: The lower limit of perpetual snow is called the ‘snowline’. The snowline in the Himalayas has different heights in different parts, depending on latitude, altitude, amount of precipitation, moisture, slope and local topography.

1. The snowline in the Western Himalaya is at a lower altitude than in the Eastern Himalaya. E.g. while the glaciers of the Kanchenjunga in the Sikkim portion hardly move below 4000m, and those of Kumaon and Lahul to 3600m, the glaciers of the Kashmir Himalayas may descend to 2500m above the sea level.

- It is because of the increase in latitude from 28°N in Kanchenjunga to 36°N in the Karakoram (Lower latitude —> warmer temperatures —> higher snowline).

- Also, the Eastern Himalayas rise abruptly from the planes without the intervention of High ranges.

- Though the total precipitation is much less in the western Himalayas, it all takes place in the form of snow.

2. In the Great Himalayan ranges, the snowline is at a lower elevation on the southern slopes than on the northern slopes. This is because the southern slopes are steeper and receive more precipitation as compared to the northern slopes.

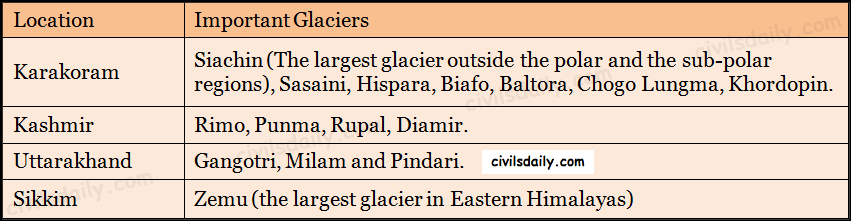

Glaciers: The main glaciers are found in the Great Himalayas and the Trans-Himalayan ranges (Karakoram, Ladakh and Zaskar). The Lesser Himalayas have small glaciers, though traces of large glaciers are found in the Pir Panjal and Dhauladhar ranges. Some of the important glaciers are:

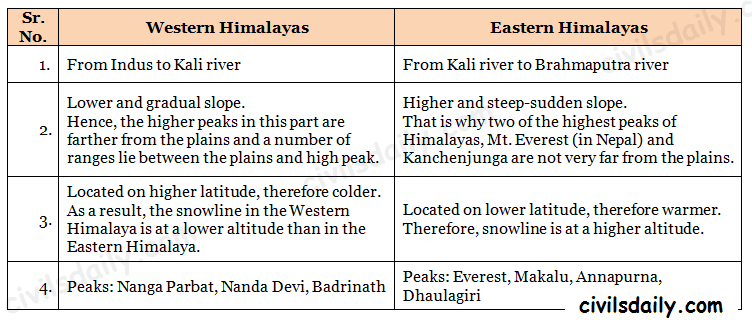

Key differences between the Eastern and Western Himalayas:

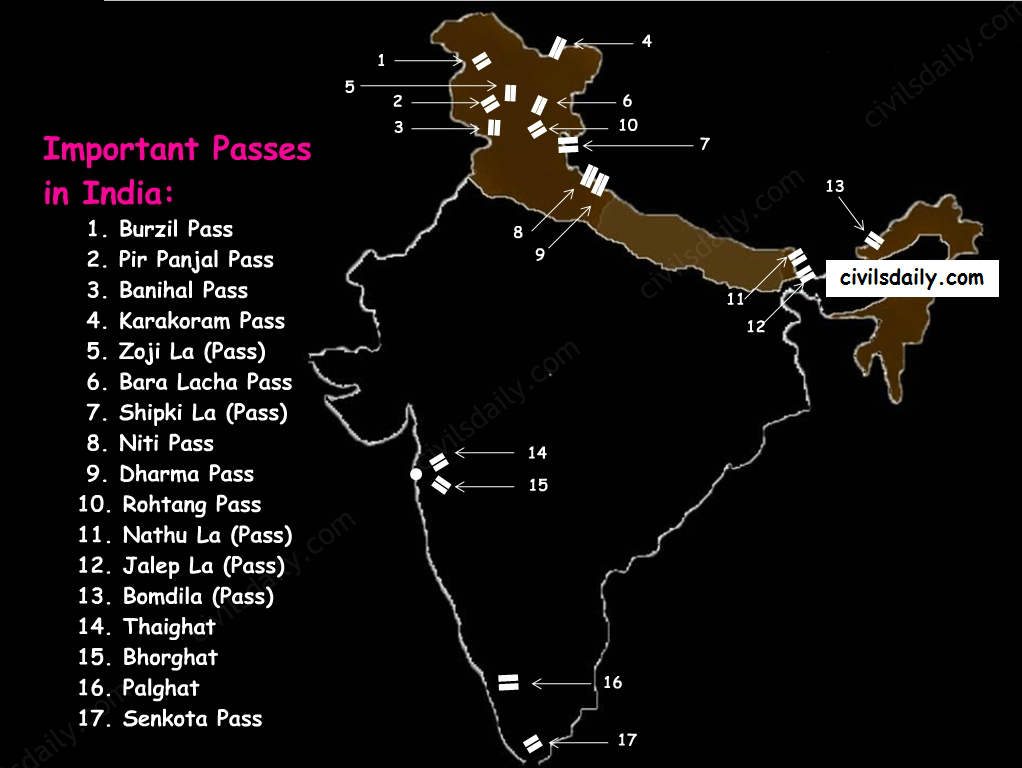

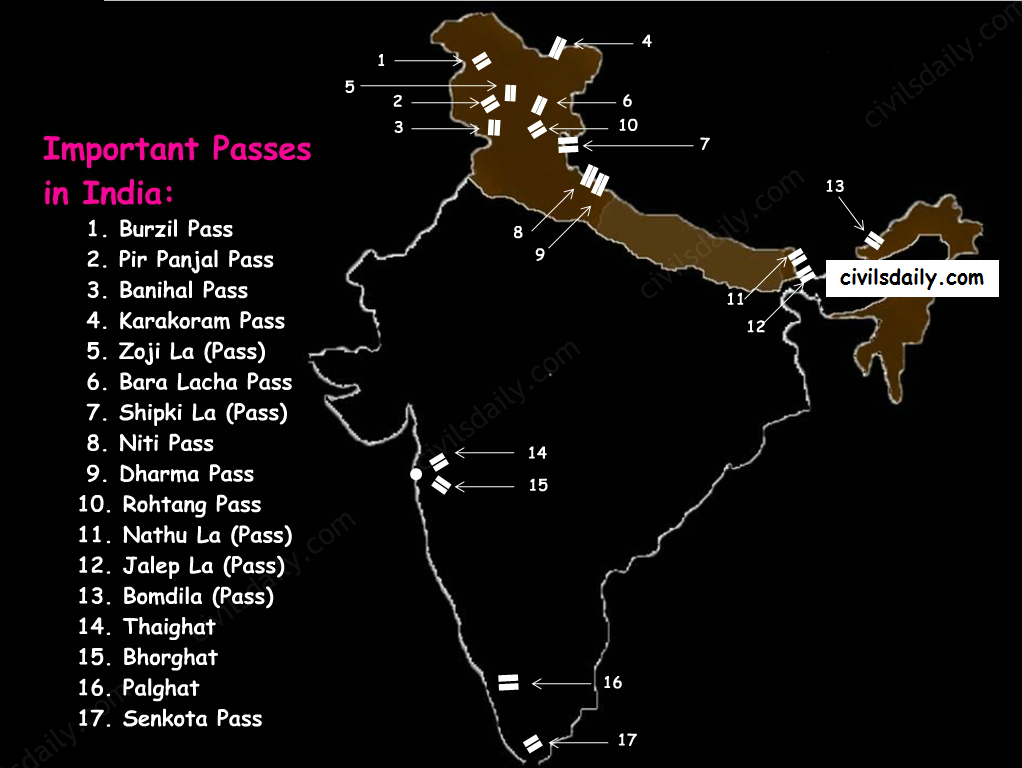

Important Passes in India:

A pass is a narrow gap in a mountain range which provides a passageway through the barrier.

- Pir Panjal Pass – It provides the shortest and the easiest metal road between Jammu and the Kashmir Valley. But this route had to be closed down as a result of partition of the subcontinent.

- Banihal Pass – It is in Jammu and Kashmir. The road from Jammu to Srinagar transversed Banihal Pass until 1956 when Jawahar Tunnel was constructed under the pass. The road now passes through the tunnel and the Banihal Pass is no longer used for road transport.

- Zoji La (Pass) – It is in the Zaskar range of Jammu and Kashmir. The land route from Srinagar to Leh goes through this pass.

- Shipki La (Pass) – It is in Himachal Pradesh. The road from Shimla to Tibet goes through this pass. The Satluj river flows through this pass.

- Bara Lacha Pass – It is also in Himachal Pradesh. It links Mandi and Leh by road.

- Rohtang Pass – It is also in Himachal Pradesh. It cuts through the Pir Panjal range. It links Manali and Leh by road.

- Niti Pass – It is in Uttarakhand. The road to the Kailash and the Manasarovar passes through it.

- Nathu La (Pass) – It is in Sikkim. It gives way to Tibet from Darjeeling and Chumbi valley. The Chumbi river flows through this pass.

- Jalep La (Pass) – At the tri-junction of India- China-Bhutan. The Teesta river has created this pass.

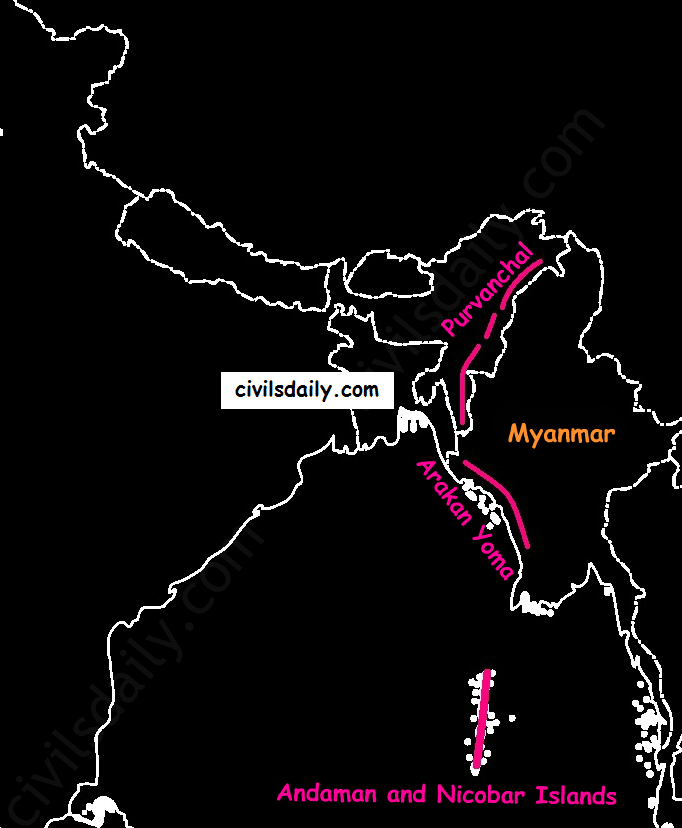

B) The North-Eastern Hills and Mountains

The Brahmaputra marks the eastern border of Himalayas. Beyond the Dihang gorge, the Himalayas bend sharply towards the south and form the Eastern hills or Purvanchal.

- These hills run through the northeastern states of India.

- These hills differ in scale and relief but stem from the Himalayan orogeny.

- They are mostly composed of sandstones (i.e. Sedimentary rocks).

- These hills are covered with dense forests.

- Their elevation decreases from north to south. Although comparatively low, these hill ranges are rather forbidding because of the rough terrain, dense forests and swift streams.

- Purvanchal hills are convex to the west.

- These hills are composed of:

- Patkai Bum – Border between Arunachal Pradesh and Myanmar

- Naga Hills

- Manipuri Hills – Border between Manipur and Myanmar

- Mizo Hills.

- Patkai Bum and Naga Hills form the watershed between India and Myanmar.

- Extension of Purvanchal continues in Myanmar as Arakan Yoma –then Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

The importance of Himalayan Region:

- Climatic Influence – The altitude of the Himalayas, their sprawl and extension intercept the summer monsoon. They also prevent the cold Siberian air masses from entering into India.

- Defence

- Source of perennial rivers

- Source of fertile soils

- Generation of hydroelectricity

- Forest wealth

- Orchards

- Minerals – The Himalayan region is rich in minerals e.g. gold, silver, copper, lead etc. are known to occur. Coal is found in Kashmir. But at the present level of technological advancement, it is not possible to extract these minerals. Also, it is not economically viable.

- Tourism

- Pilgrimage

NORTHERN PLAINS

Location and Extent:

Northern plains are the youngest physiographic feature in India. They lie to the south of the Shivaliks, separated by the Himalayan Frontal Fault (HFF). The southern boundary is a wavy irregular line along the northern edge of the Peninsular India. On the eastern side, the plains are bordered by the Purvanchal hills.

Formation of Northern Plains:

Due to the uplift of the Himalayas in the Tethys Sea, the northern part of the Indian Peninsula got subsided and formed a large basin.

That basin was filled with sediments from the rivers which came from the mountains in the north and from the peninsula in the south. These extensive alluvial deposits led to the formation of the northern plains of India.

Chief Characteristics:

- The northern plain of India is formed by three river systems, i.e. the Indus, the Ganga and the Brahmaputra; along with their tributaries.

- The northern plains are the largest alluvial tract of the world. These plains extend approximately 3200 km from west to east.

- The average width of these plains varies between 150 and 300 km. In general, the width of the northern plains increases from east to west (90-100km in Assam to about 500km in Punjab).

- The exact depth of alluvium has not yet been fully determined. According to recent estimates, the average depth of alluvium in the southern side of the plain varies between 1300-1400m, while towards the Shiwaliks, the depth of alluvium increases. The maximum depth of over 8000m has been reached in parts of Haryana.

- The extreme horizontality of this monotonous plain is its chief characteristic (200m – 291m). The highest elevation of 291 m above mean sea level near Ambala forms a watershed between the Indus system and Ganga system).

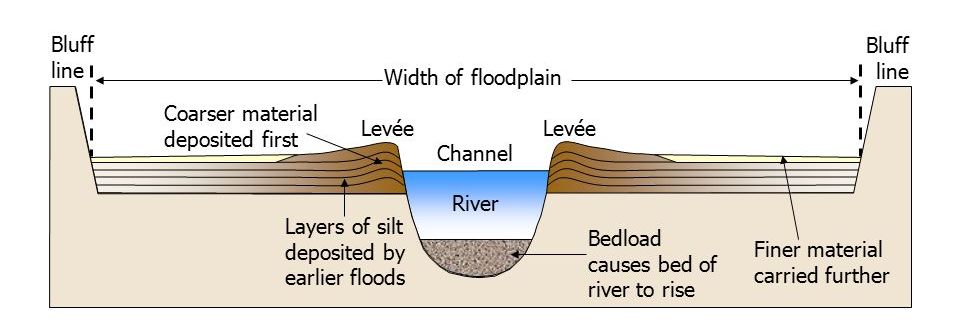

- The monotony of the physical landscape is broken at the micro-level by the river bluffs, levees etc.

- [Floodplain – That part of a river valley, adjacent to the channel, over which a river flows in times of a flood.

- Levee – An elevated bank flanking the channel of the river and standing above the level of the flood plain.

- Bluff – A river cut cliff or steep slope on the outside of a meander. A line of bluffs often marks the edge of a former floodplain.]

Physiographic Divisions of the Northern Plains:

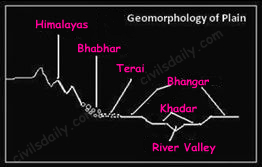

From the north to the south, the northern plains can be divided into three major zones:

- The Bhabar

- The Tarai

- The alluvial plains.

The alluvial plains can be further divided into the Khadar and the Bhangar as illustrated below:

Let’s understand these divisions one by one:

Bhabar:

- Bhabar is a narrow belt (8-10km wide) which runs in the west-east direction along the foot of the Himalayas from the river Indus to Teesta.

Source - Rivers which descend from the Himalayas deposit their load along the foothills in the form of alluvial fans.

- These fans consisting of coarser sediments have merged together to build up the piedmont plain/the Bhabar.

- The porosity of the pebble-studded rock beds is very high and as a result, most of the streams sink and flow underground. Therefore, the area is characterized by dry river courses except in the rainy season.

- The Bhabar track is not suitable for cultivation of crops. Only big trees with large roots thrive in this region.

- The Bhabar belt is comparatively narrow in the east and extensive in the western and north-western hilly region.

Tarai:

- It is a 10-20 km wide marshy region in the south of Bhabar and runs parallel to it.

- The Tarai is wider in the eastern parts of the Great Plains, especially in the Brahmaputra valley due to heavy rainfall.

- It is characterized by the re-emergence of the underground streams of the Bhabar belt.

- The reemerged water transforms large areas along the rivers into badly drained marshy lands.

- Once covered with dense forests, most of the Tarai land (especially in Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand) has been reclaimed and turned into agricultural land over a period of time.

Bhangar:

- It is the older alluvium along the river beds forming terraces higher than the flood plain.

- Dark in colour, rich in humus content and productive.

- The soil is clayey in composition and has lime modules (called kankar)

- Found in doabs (inter-fluve areas)

- ‘The Barind plains’ in the deltaic region of Bengal and the ‘bhur formations’ in the middle Ganga and Yamuna doab are regional variations of Bhangar. [Bhur denotes an elevated piece of land situated along the banks of the Ganga river especially in the upper Ganga-Yamuna Doab. This has been formed due to accumulation of wind-blown sands during the hot dry months of the year]

- In relatively drier areas, the Bhangar also exhibits small tracts of saline and alkaline efflorescence known as ‘Reh’, ‘Kallar’ or ‘Bhur’. Reh areas have spread in recent times with an increase in irrigation (capillary action brings salts to the surface).

- May have fossil remains of even those plants and animals which have become extinct.

Khadar:

- Composed of newer alluvium and forms the flood plains along the river banks.

- Light in colour, sandy in texture and more porous.

- Found near the riverbeds.

- A new layer of alluvium is deposited by river flood almost every year. This makes them the most fertile soils of Ganges.

- In Punjab, the Khadar rich flood plains are locally known as ‘Betlands’ or ‘Bets’.

- The rivers in Punjab-Haryana plains have broad flood plains of Khadar flanked by bluffs, locally known as Dhayas. These bluffs are as high as 3metres.

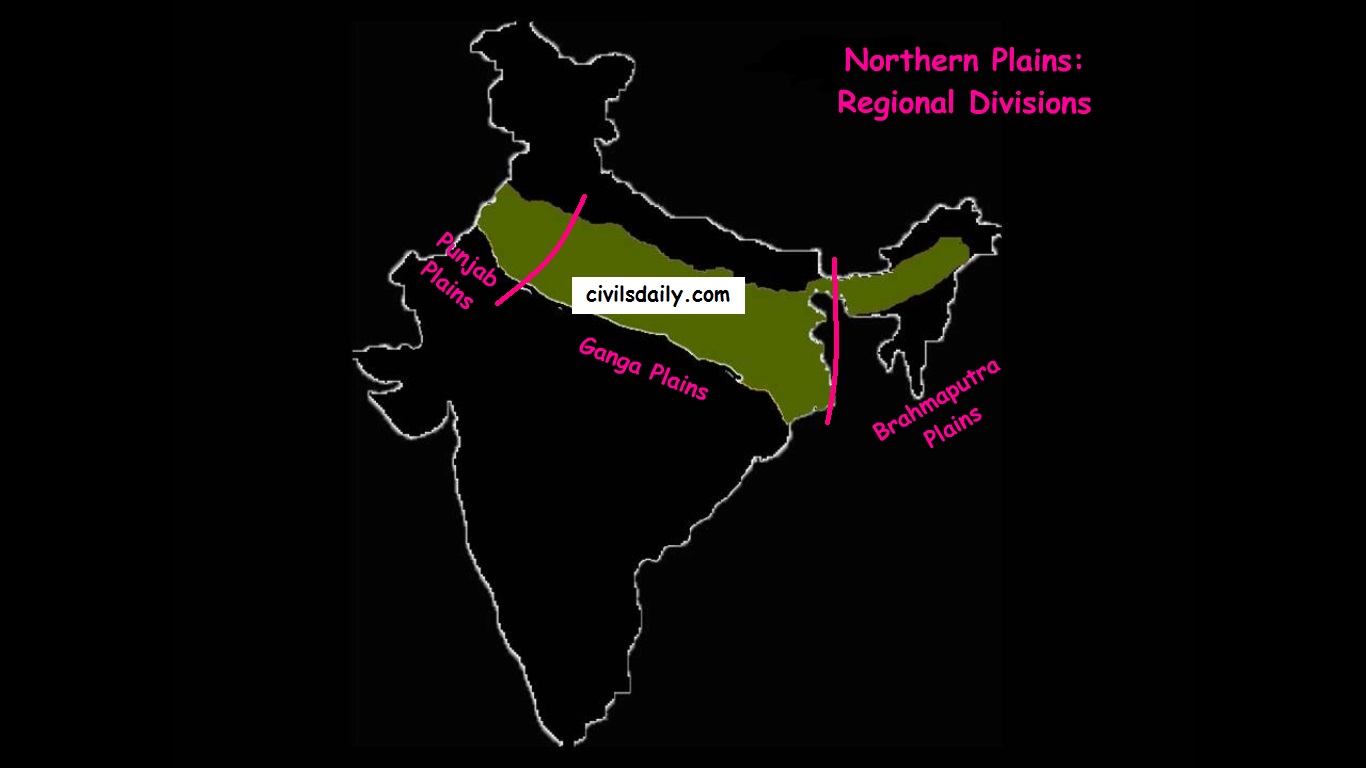

Northern Plain: Regional Divisions

The Regional Divisions of the Northern Plains: Punjab, Ganga and the Brahmaputra Plains.

- Punjab Plains:

- The Punjab plains form the western part of the northern plain.

- In the east, the Delhi-Aravalli ridge separates it from the Ganga plains.

- This is formed by the Indus and its tributaries; like Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas and Sutlej. A major portion of these plains is in Pakistan.

- It is divided into many Doabs (do-“two” + ab- “water or river” = “a region or land lying between and reaching to the meeting of the two rivers”).

Khadar and Bhangar - Important features:

- Khadar rich flood plains known as ‘Betlands’ or ‘Bets’.

- The rivers in Punjab-Haryana plains have broad flood plains of Khadar flanked by bluffs, locally known as Dhayas.

- The northern part of this plane adjoining the Shivalik hills has been heavily eroded by numerous streams, which are called Chhos.

- The southwestern parts, especially the Hisar district is sandy and characterized by shifting sand-dunes.

- Ganga Plains:

- The Ganga plains lie between the Yamuna catchment in the west to the Bangladesh border in the East.

- The lower Ganga plain has been formed by the down warping of a part of Peninsular India between Rajmahal hills and the Meghalaya plateau and subsequent sedimentation by the Ganga and Brahmaputra rivers.

- The main topographical variations in these plains include Bhabar, Tarai, Bhangar, Khadar, levees, abandoned courses etc.

- Almost all the rivers keep on shifting their courses making this area prone to frequent floods. The Kosi river is very notorious in this respect. It has long been called the ‘Sorrow of Bihar’.

- The northern states, Haryana, Delhi, UP, Bihar, part of Jharkhand and West Bengal in the east lie in the Ganga plains.

- The Ganga-Brahmaputra delta: the largest delta in the world. A large part of the coastal delta is covered tidal forests called Sunderbans. Sunderbans, the largest mangrove swamp in the world gets its name from the Sundari tree which grows well in marshland. It is home to the Royal Tiger and crocodiles.

- Brahmaputra Plains:

- This plain forms the eastern part of the northern plain and lies in Assam.

- Its western boundary is formed by the Indo-Bangladesh border as well as the boundary of the lower Ganga Plain. Its eastern boundary is formed by Purvanchal hills.

- The region is surrounded by high mountains on all sides, except on the west.

- The whole length of the plain is traversed by the Brahmaputra.

- The Brahmaputra plains are known for their riverine islands (due to the low gradient of the region) and sand bars.

- The innumerable tributaries of the Brahmaputra river coming from the north form a number of alluvial fans. Consequently, the tributaries branch out in many channels giving birth to river meandering leading to the formation of bill and ox-bow lakes.

- There are large marshy tracts in this area. The alluvial fans formed by the coarse alluvial debris have led to the formation of terai or semi-terai conditions.

Significance of this region:

- The plains constitute less than one-third of the total area of the country but support over 40 percent of the total population of the country.

- Fertile alluvial soils, flat surface, slow-moving perennial rivers and favourable climate facilitate an intense agricultural activity.

- The extensive use of irrigation has made Punjab, Haryana and western part of Uttar Pradesh the granary of India (Prairies are called the granaries of the world).

- Cultural tourism: Several sacred places and centres of pilgrimage are situated in these plains e.g. Haridwar, Amritsar, Varanasi, Allahabad, Bodh Gaya etc.

- The sedimentary rocks of plains have petroleum and natural gas deposits.

- The rivers here have very gentle gradients which make them navigable over long distances.

PENINSULAR PLATEAU

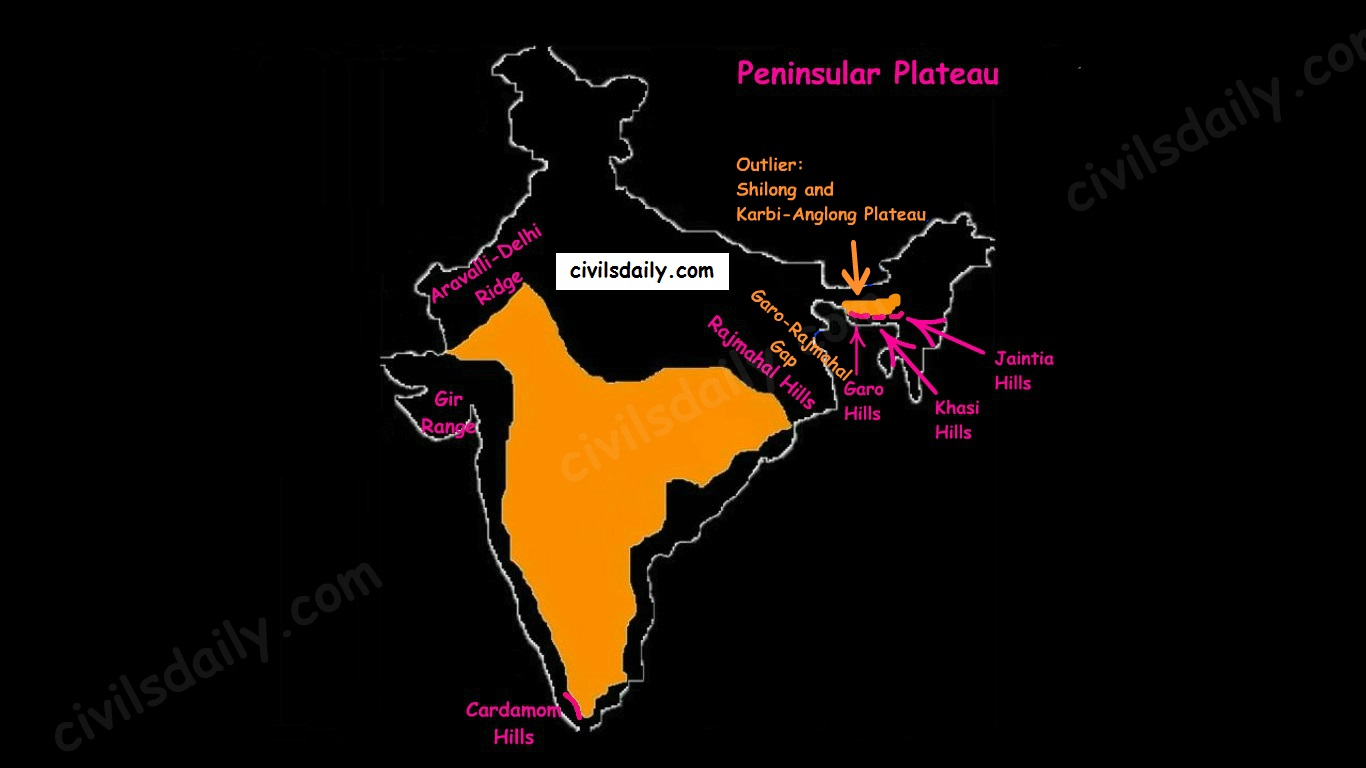

A. Location and Extent

- The Peninsular Plateau lies to the south of the Northern Plains of India.

- It is bordered on all sides by the hill ranges:

- Delhi ridge in the north-west (extension of Aravalis),

- the Rajmahal Hills in the east,

- Gir range in the west, and

- the Cardamom Hills in the south constitute the outer extent of the peninsular plateau.

- Outlier:

- Shillong and Karbi-Anglong plateau.

Note: Kutchch Kathiawar region – The region, though an extension of Peninsular plateau (because Kathiawar is made of the Deccan Lava and there are tertiary rocks in the Kutch area), they are now treated as an integral part of the Western Coastal Plains as they are now levelled down.

- The Garo-Rajmahal Gap:

- The two disconnected outlying segments of the plateau region are seen in the Rajmahal and Garo-Khasi Jaintia hills.

- It is believed that due to the force exerted by the northeastward movement of the Indian plate at the time of the Himalayan origin, a huge fault was created between the Rajmahal hills and the Meghalaya plateau

- Later, this depression got filled up by the deposition activity of the numerous rivers.

- As a result, today the Meghalaya and Karbi Anglong plateau stand detached from the main Peninsular Block.

Geological History and Features:

The peninsular plateau is a tableland which contains igneous and metamorphic rocks. It is one of the oldest and the most stable landmass of India.

In its otherwise stable history, the peninsula has seen a few changes like:

- Gondwana Coal Formation.

- Narmada-Tapi rift valley formation.

- Basalt Lava eruption on Deccan plateau:

During its journey northward after breaking off from the rest of Gondwana, the Indian Plate passed over a geologic hotspot, the Réunion hotspot, which caused extensive melting underneath the Indian Craton. The melting broke through the surface of the craton in a massive flood basalt event, creating what is known as the Deccan Traps (Its various features have been discussed in the later portion of the article).

Chief Characteristics:

The entire peninsular plateau region is an aggregation of several smaller plateaus and hill ranges interspersed with river basins and valleys. The Chhattisgarh plain occupied by the dense Dandakaranya forests is the only plain in the peninsula.

1. General elevation and flow of rivers:

- The average elevation is 600-900 metres.

- The general elevation of the plateau is from the west to the east, which is also proved by the pattern of the flow of rivers.

- Barring Narmada and Tapti all the major rivers lying to the south of the Vindhyas flow eastwards to fall into the Bay of Bengal.

- The westward flow of Narmada and Tapi is assigned to the fact that they have been flowing through faults or rifts which were probably caused when the Himalayas began to emerge from the Tethys Sea of the olden times.

2. Some of the important physiographic features of this region are:

- Tors – Prominent, isolated mass of jointed, weathered rock, usually granite.

- Block Mountains and Rift Valleys:

- Spurs: A marked projection of land from a mountain or a ridge

- Bare rocky structures,

- Series of hummocky hills and wall-like quartzite dykes offering natural sites for water storage.

- Broad and shallow valleys and rounded hills

- Ravines and gorges: The northwestern part of the plateau has a complex relief of ravines and gorges. The ravines of Chambal, Bhind and Morena are some of the well-known examples.

3. The Deccan Traps:

- One of the most important features of the peninsular plateau is the black soil area in the western and northwestern part of the plateau, which is known as the Deccan Trap.

- From the end of the Cretacious until the beginning of the Eocene, numerous fissure-type eruptions took place in the north-western part of the Deccan plateau. It is believed that the lava outpourings were more than the mass comprising the present-day Himalayas.

- It covers a major portion of the Maharashtra plateau and parts of Gujarat, northern Karnataka and Malwa plateau. Some parts of Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, UP, and Jharkhand have some outliers of Deccan trap.

- Basalt is the main rock of the region.

- The region has black cotton soil as a result of weathering of this lava material and this soil is one of the finest examples of the parent material controlled soils.

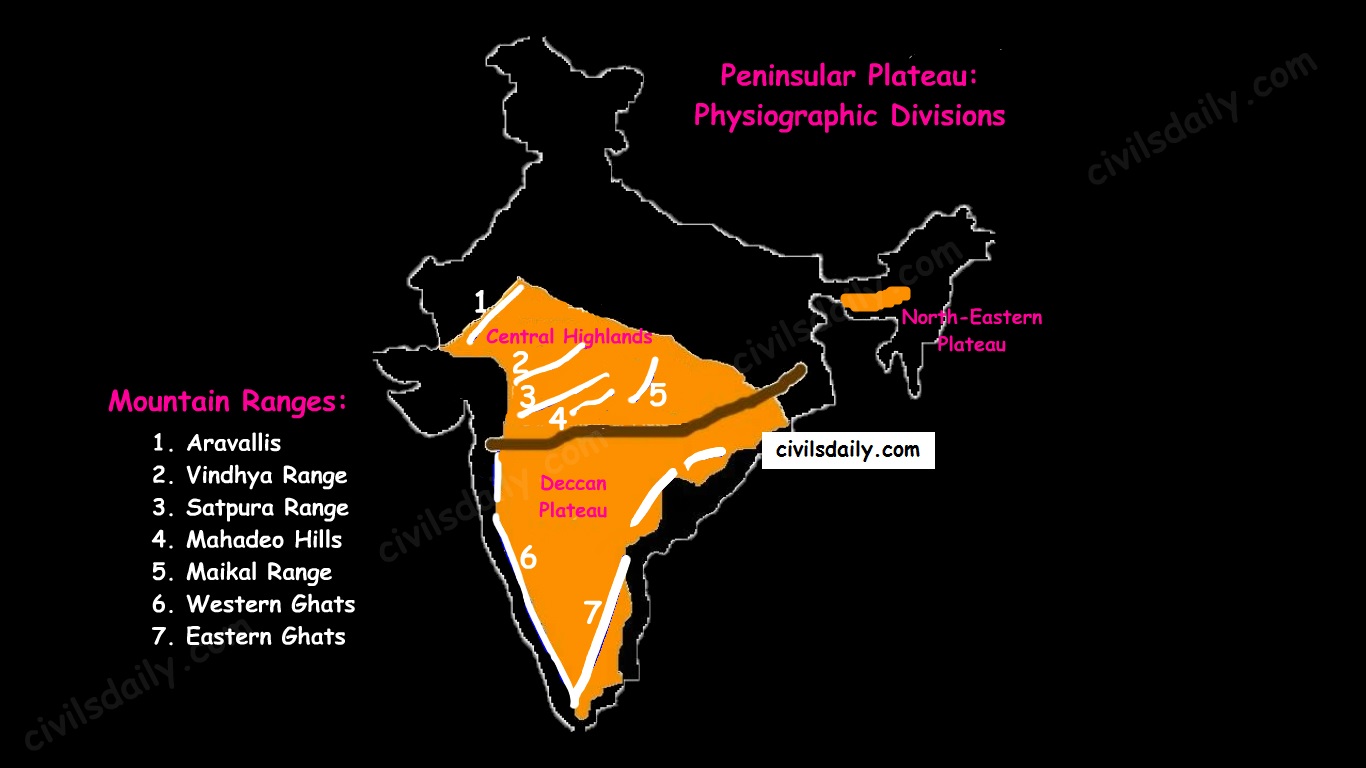

Physiographic Divisions:

On the basis of prominent relief features, the peninsular plateau can be divided into three broad groups:

- The Central Highlands

- The Deccan Plateau

- The Northeastern Plateau.

Let’s take up these divisions one by one:

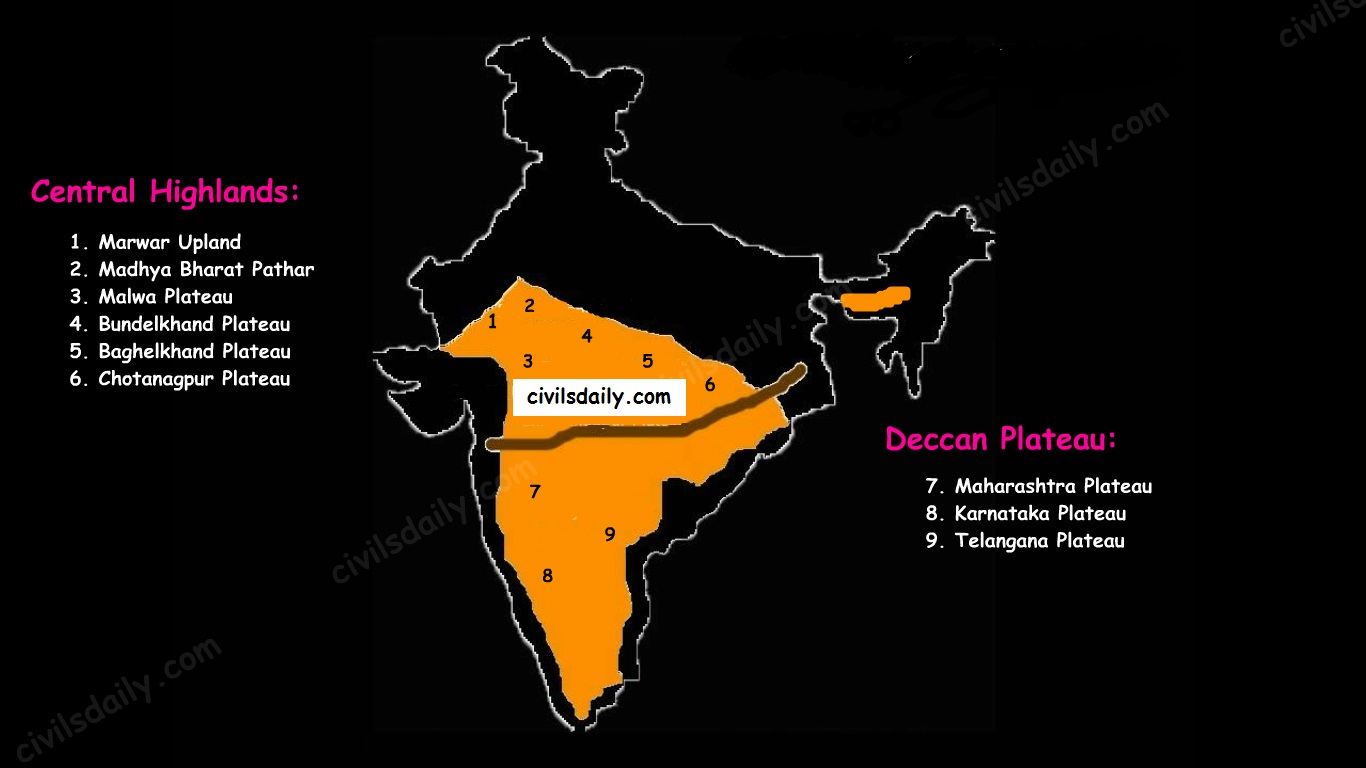

1. The Central Highlands

- The northern segment of the peninsular plateau is known as the Central Highlands.

- Location:

- North of Narmada river.

- They are bounded to the west by the Aravallis.

- Satpura ranges (formed by a series of scarped plateaus) lie in the South.

- General Elevation: 700-1,000 m above the mean sea level and it slopes towards the north and northeastern directions.

- These highlands consist of the:

- Marwar upland – to the east of Aravallis in Rajasthan

- A rolling plain carved by Banas river. [Rolling Plain: ‘Rolling plains’ are not completely flat; there are slight rises and fall in the landform. Ex: Prairies of USA]

- The average elevation is 250-500 m above sea level.

- Madhya Bharat Pathar – to the east of Marwar upland.

- Malwa plateau – It lies in Madhya Pradesh between Aravali and Vindhyas. It is composed of the extensive lava flow and is covered with black soils.

- Bundelkhand plateau – It lies along the borders of UP and MP. Because of intensive erosion, semi-arid climate and undulating area, it is unfit for cultivation.

- Baghelkhand plateau – It lies to the east of the Maikal range.

- Chhotanagpur plateau – the northeast part of Peninsular plateau.

- It Includes Jharkhand, parts of Chhattisgarh and West Bengal.

- This plateau consists of a series of step-like sub-plateaus (locally called peatlands – high-level plateau). It is thus famous as the Patland plateau and known as Ruhr of India.

- Rajmahal Hills are the northeastern projection of Chhota Nagpur Plateau.

- It is a mineral-rich plateau.

- Marwar upland – to the east of Aravallis in Rajasthan

- The extension of the Peninsular plateau can be seen as far as Jaisalmer in the West, where it has been covered by the longitudinal sand ridges and crescent-shaped sand dunes called barchans.

- This region has undergone metamorphic processes in its geological history, which can be corroborated by the presence of metamorphic rocks such as marble, slate, gneiss, etc.

- Most of the tributaries of the river Yamuna have their origin in the Vindhyan and Kaimur ranges. Banas is the only significant tributary of the river Chambal that originates from the Aravalli in the west.

2. The Deccan Plateau

- The Deccan Plateau lies to the south of the Narmada River and is shaped as an inverted triangle.

- It is bordered by:

- The Western Ghats in the west,

- The Eastern Ghats in the east,

- The Satpura, Maikal range and Mahadeo hills in the north.

- It is volcanic in origin, made up of horizontal layers of solidified lava forming trap structure with step-like appearance. The sedimentary layers are also found in between the layers of solidified lava, making it inter–trapping in structure.

- Most of the rivers flow from west to east.

- The plateau is suitable for the cultivation of cotton; home to rich mineral resources and a source to generate hydroelectric power.

- The Deccan plateau can be subdivided as follows:

- The Maharashtra Plateau – it has typical Deccan trap topography underlain by basaltic rock, the regur.

- The Karnataka Plateau (also known as Mysore plateau) – divided into western hilly country region of ‘Malnad’ and plain ‘Maidan’

- Telangana Plateau

3. The Northeastern Plateau:

- The Meghalaya (or Shillong) plateau is separated from peninsular rock base by the Garo-Rajmahal gap.

- Shillong (1,961 m) is the highest point of the plateau.

- The region has the Garo, Khasi, Jaintia and Mikir (Rengma) hills.

- An extension of the Meghalaya plateau is also seen in the Karbi Anglong hills of Assam.

- The Meghalaya plateau is also rich in mineral resources like coal, iron ore, sillimanite, limestone and uranium.

- This area receives maximum rainfall from the south-west monsoon. As a result, the Meghalaya plateau has a highly eroded surface. Cherrapunji displays a bare rocky surface devoid of any permanent vegetation cover.

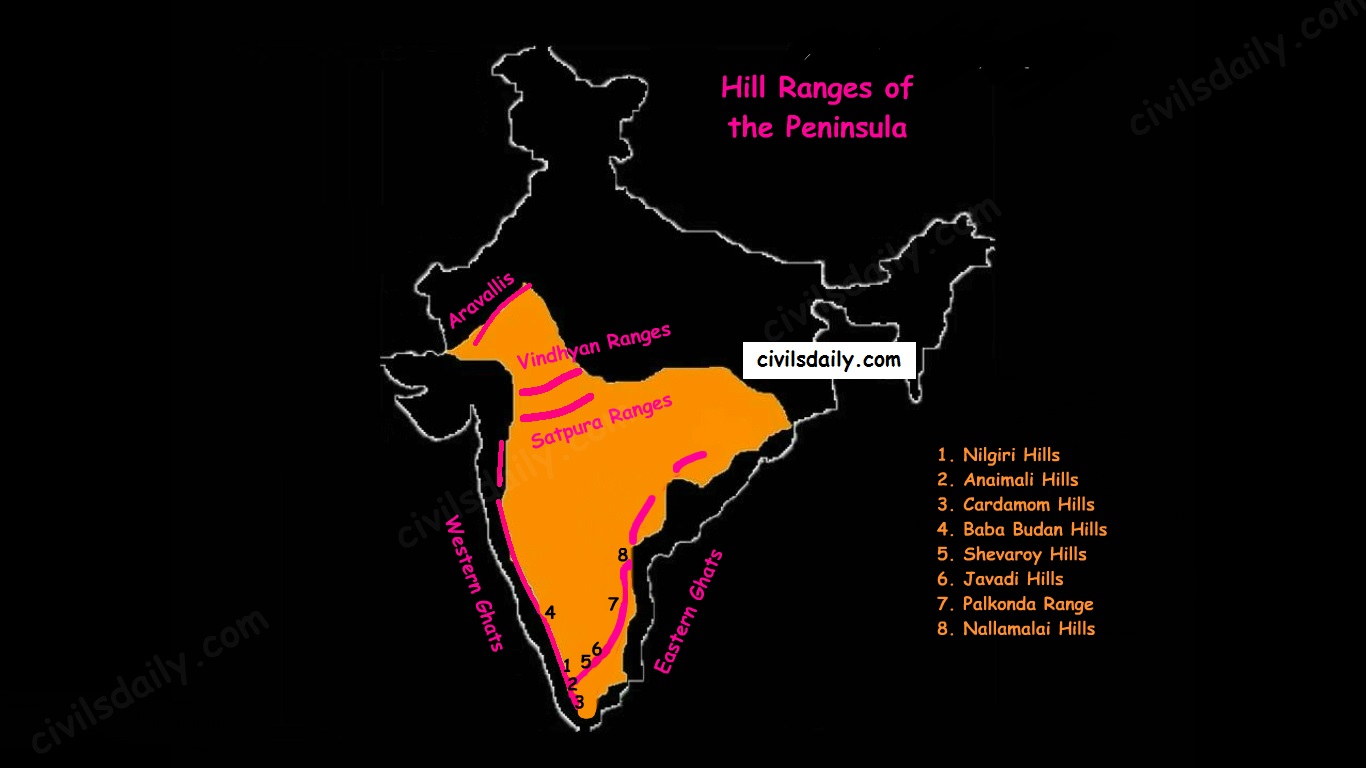

Hill ranges of the peninsula:

Most of the hills in the peninsular region are of the relict type (residual hills). They are the remnants of the hills and horsts formed many million years ago (horst: uplifted block; graben: subsided block).

The plateaus of the Peninsular region are separated from one another by these hill ranges and various river valleys.

1. The Aravalli Mountain Range:

- It is a relic of one of the oldest fold mountains of the world.

- Its general elevation is only 400-600 m, with few hills well above 1,000 m.

- At present, it is seen as a discontinuous ridge from Delhi to Ajmer and rising up to 1722m (Gurushikhar peak in Mount Abu) and thence southward.

- It is known as ‘Jarga’ near Udaipur and ‘Delhi Ridge’ near Delhi.

- Dilwara Jain Temple, the famous Jain temple is situated on Mt. Abu.

2. Vindhyan Ranges:

- They rise as an escarpment running parallel to the Narmada-Son valley.

- General elevation: 300 to 650 m.

- Most of them are made up of sedimentary rocks of ancient ages.

- They act as a watershed between Gangetic and peninsular river systems.

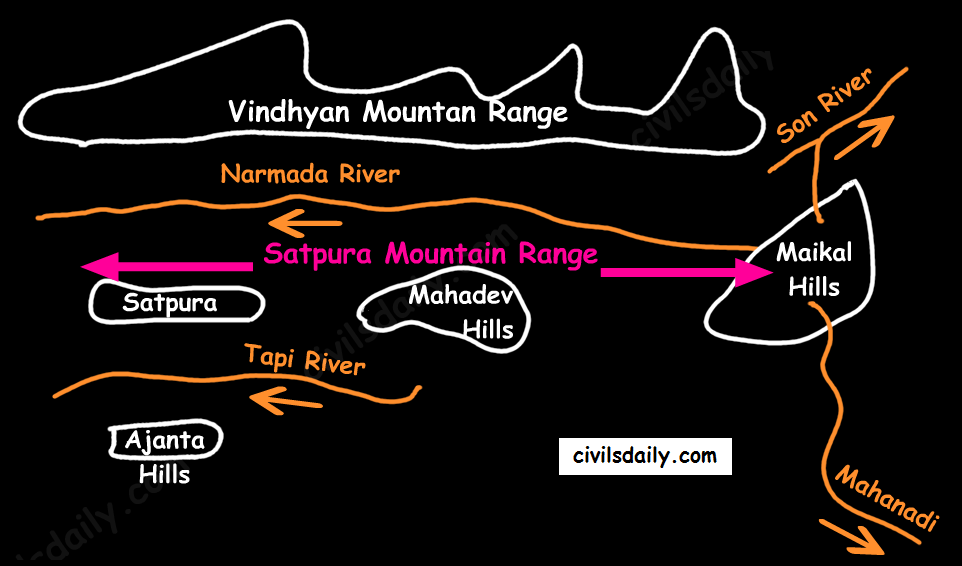

3. Satpura ranges:

- Satpura range is a series of seven mountains (‘Sat’ = seven and ‘pura’ = mountains).

- The seven mountain ranges or folds of Satpura’s are:

- Maikal Hills

- Mahadeo Hills near Pachmarhi

- Kalibhit

- Asirgarh

- Bijagarh

- Barwani

- Arwani which extends to Rajpipla Hills in Eastern Gujarat.

- Satpura ranges run parallel between Narmada and Tapi, parallel to Maharashtra-MP border.

- Dhupgarh (1,350 m) near Pachmarhi on Mahadev Hills is the highest peak of the Satpura Range.

- Amarkantak (1,127 m) is another important peak. Amarkantak is the highest peak of the Maikal Hills from where two prominent rivers – the Narmada and the Son originate.

- Note that three rivers originate from the three sides of Maikal hills (as shown in the following map) but, from Amarkantak, only two rivers (the Narmada and the Son) originate (and not Mahanadi).

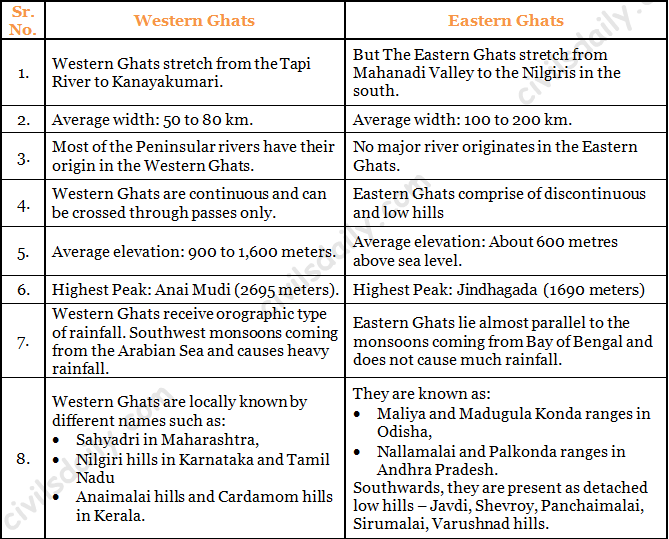

4. Western and Eastern Ghats:

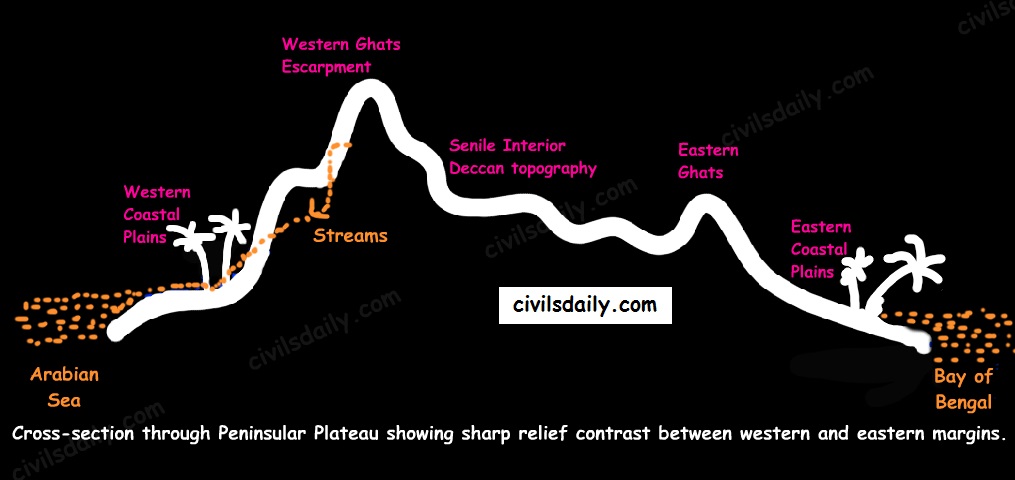

- The Western Ghats:

- These are a faulted part of the Deccan plateau running parallel from the Tapi valley to a little north of Kanyakumari (1600km). Their western slope is like an escarpment while eastern slope merges gently with the plateau.

- Their average elevation is about 1,500 m with the height increasing from north to south.

- The Eastern Ghats are in the form of residual mountains which are not regular but broken at intervals.

- The Eastern and the Western Ghats meet each other at the Nilgiri hills.

- A brief comparison between them:

Note: The Western Ghats are continuous and can be crossed through passes only. There are four main passes which have developed in the Western Ghats. These are:

- Thal Ghat – It links Nasik to Mumbai.

- Bhor Ghat – It links Mumbai to Pune.

- Pal Ghat – This pass is located between the Nilgiris and the Annamalai mountains. It is in Kerala and connects Kochi and Chennai.

- Senkota Pass – This pass located between the Nagercoil and the Cardamom hills links Thiruvananthapuram and Madurai.

For the geographical location of these passes, see the following map:

Significance of the Peninsular Region:

- Rich in mineral resources: The peninsular region of India is rich in both metallic and non-metallic minerals. About 98% of the Gondwana coal deposits of India are found in the peninsular region.

- Agriculture: Black soil found in a substantial part of the peninsula is conducive for the cultivation of cotton, maize , citrus fruits etc. Some areas are also suitable for the cultivation of tea, coffee, groundnut etc.

- Forest Products: Apart from teal, sal wood and other forest products, the forests of Western and Eastern Ghats are rich in medicinal plants and are home to many wild animals.

- Hydel Power: many rivers, which have waterfalls. They help in the generation of hydroelectric power.

- Tourism: There are numerous hill stations and hill resorts like Ooty, Mahabaleshwar, Khandala, etc.

THE INDIAN DESERT

The Indian desert is also known as the Thar Desert or the Great Indian Desert.

Location and Extent:

- Location – To the north-west of the Aravali hills.

- It covers Western Rajasthan and extends to the adjacent parts of Pakistan.

Geological History and Features

- Most of the arid plain was under the sea from Permo-Carboniferous period and later it was uplifted during the Pleistocene age. This can be corroborated by the evidence available at wood fossils park at Aakal and marine deposits around Brahmsar, near Jaisalmer (The approximate age of the wood fossils is estimated to be 180 million years).

- The presence of dry beds of rivers (eg Saraswati) indicates that the region was once fertile.

- Geologically, the desert area is a part of the peninsular plateau region but on the surface, it looks like an aggradational plain.

Chief Characteristics:

- The desert proper is called the Marusthali (dead land) as this region has an arid climate with low vegetation cover. In general, the Eastern part of the Marushthali is rocky, while its western part is covered by shifting sand dunes.

- Bagar: Bagar refers to the semi-desert area which is west of Aravallis. Bagar has a thin layer of sand. It is drained by Luni in the south whereas the northern section has a number of salt lakes.

- The Rajasthan Bagar region has a number of short seasonal streams which originate from the Aravallis. These streams support agriculture in some fertile patches called Rohi.

- Even the most important river ‘Luni’ is a seasonal stream. The Luni originates in the Pushkar valley of the Aravalli Range, near Ajmer and flows towards the southwest into the Rann of Kutch.

- The region north of Luni is known as the Thali or sandy plain.

- There are some streams which disappear after flowing for some distance and present a typical case of inland drainage by joining a lake or playa e.g. the Sambhar Lake. The lakes and the playas have brackish water which is the main source of obtaining salt.

- Well pronounced desert land features:

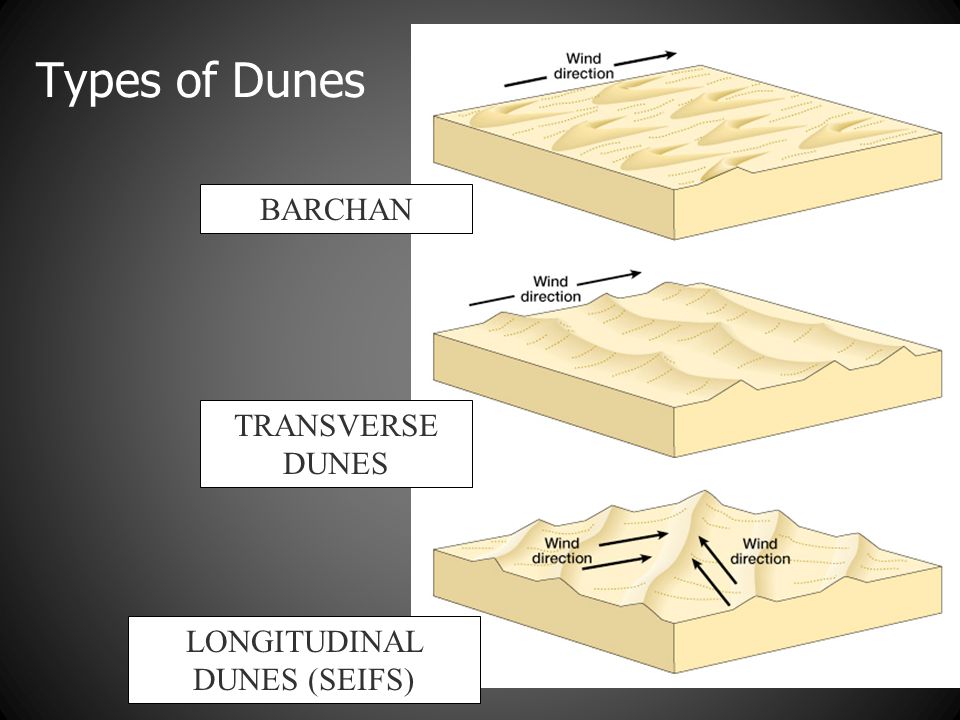

- Sand dunes: It is a land of undulating topography dotted with longitudinal dunes, transverse dunes and barchans. [Barchan – A crescent-shaped sand dune, the horns of which point away from the direction of the dominant wind; Longitudinal dune – A sand dune with its crest running parallel to the direction of prevailing wind]

- Mushroom rocks

- Shifting dunes (locally called Dhrians)

- Oasis (mostly in its southern part)

THE COASTAL PLAINS

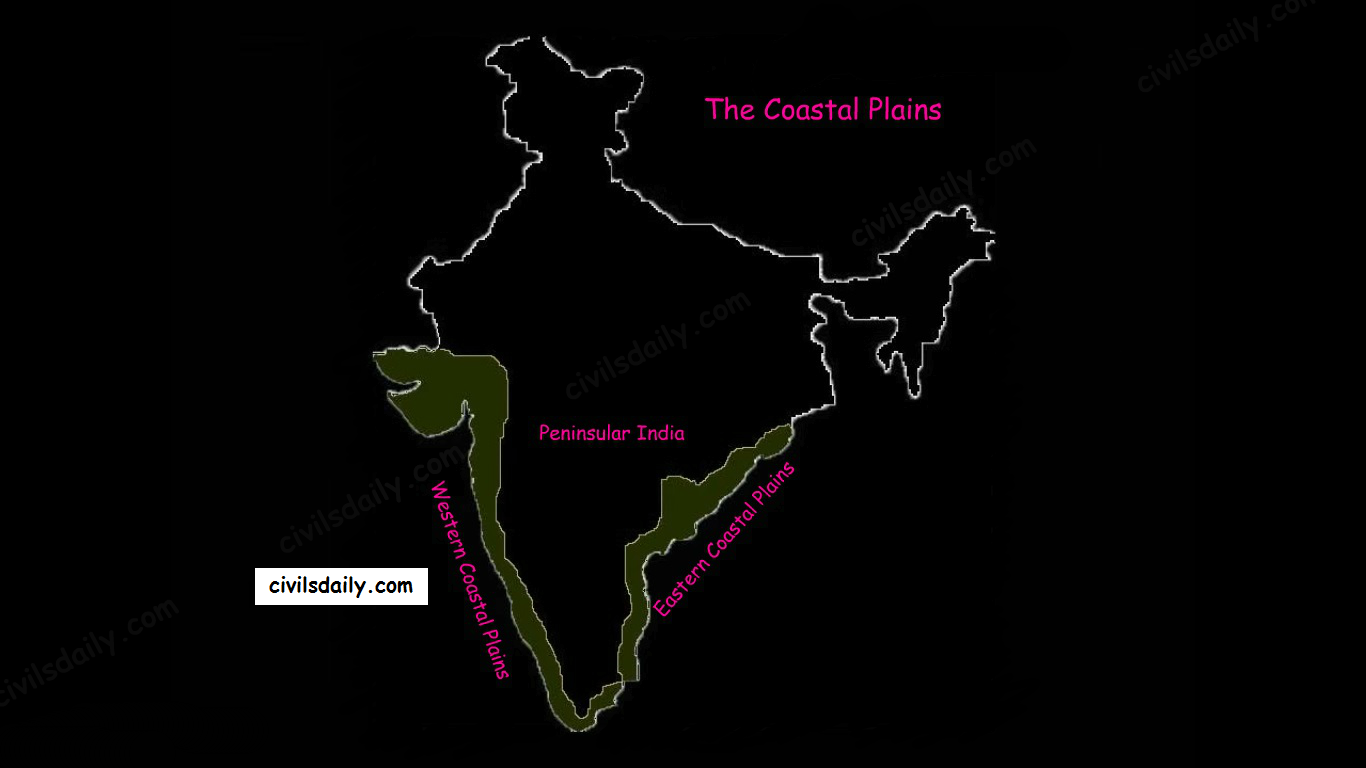

Of the total coastline of India (7517 km), that of the peninsula is 6100 km between the peninsular plateau and the sea. The peninsular plateau of India is flanked by narrow coastal plains of varied width from north to south.

On the basis of the location and active geomorphologic processes, these can be broadly divided into two parts:

- The western coastal plains

- The eastern coastal plains.

We now take them up one by one:

The Western Coastal Plain

1. Extent: The Western Coastal Plains are a thin strip of coastal plains with a width of 50 km between the Arabian Sea and the Western Ghats.

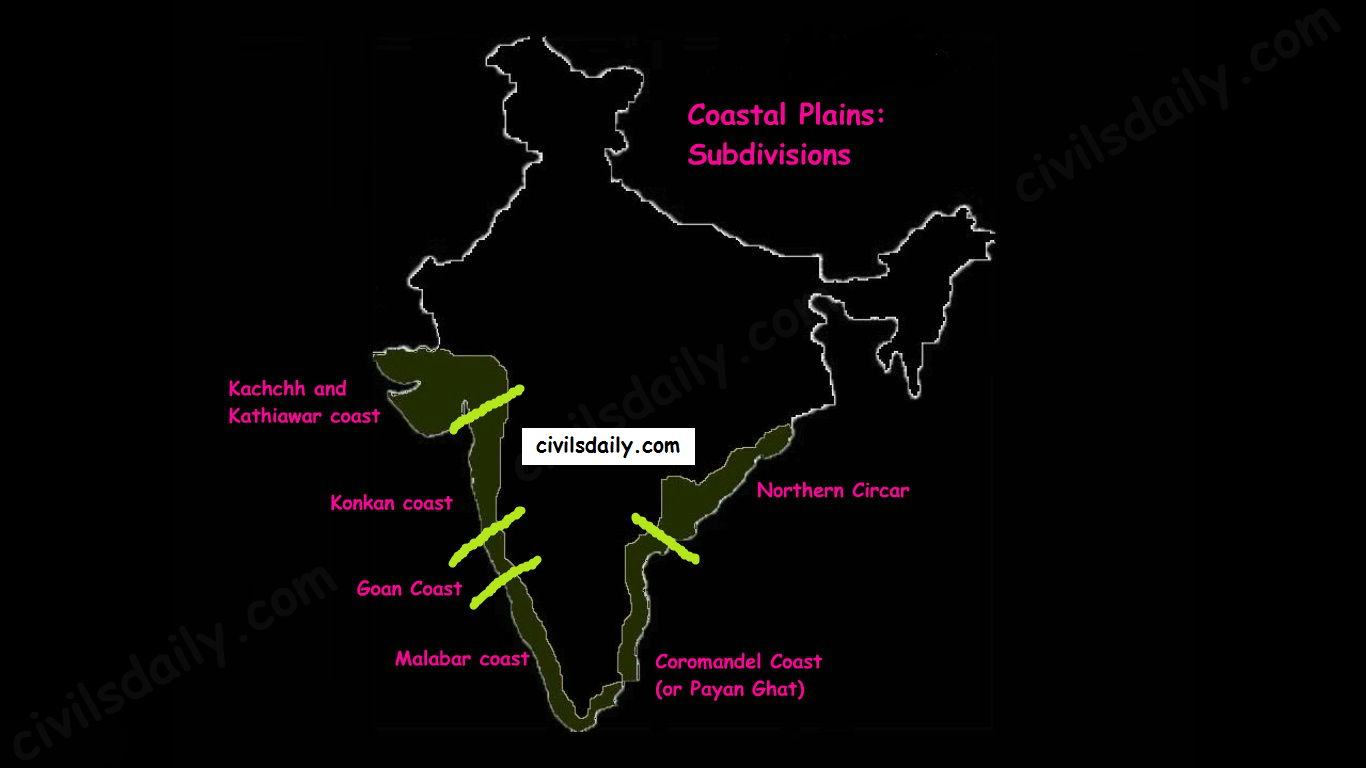

2. Subdivisions: Extending from the Gujarat coast in the north to the Kerala coast in the south, the western coast may be divided into following divisions:

- Kachchh and Kathiawar coast in Gujarat,

- Konkan coast in Maharashtra,

- Goan Coast in Karnataka, and

- Malabar coast in Kerala

Note: Kutch and Kathiawar, though an extension of Peninsular plateau (because Kathiawar is made of the Deccan Lava and there are tertiary rocks in the Kutch area), they are still treated as an integral part of the Western Coastal Plains as they are now levelled down.

3. A coastline of submergence: The western coastal plains are an example of the submerged coastal plain. It is believed that the city of Dwaraka which was once a part of the Indian mainland situated along the west coast is submerged underwater.

4. Characteristic Features:

- The western coastal plains are narrow in the middle and get broader towards north and south. Except for the Kachchh and Kathiawar coastal region, these are narrower than their eastern counterpart.

- The coast is straight and affected by the South-West Monsoon winds over a period of six months. The western coastal plains are thus wetter than their eastern counterpart.

- The western coast being more indented than the eastern coast provides natural conditions for the development of ports and harbours. Kandla, Mazagaon, JLN port Navha Sheva, Marmagao, Mangalore, Cochin, etc. are some of the important natural ports located along the west coast.

- The western coastal plains are dotted with a large number of coves (a very small bay), creeks (a narrow, sheltered waterway such as an inlet in a shoreline or channel in a marsh) and a few estuaries. The estuaries, of the Narmada and the Tapi are the major ones.

- The rivers flowing through this coastal plain do not form any delta. Many small rivers descend from the Western Ghats making a chain of waterfalls.

- The Kayals – The Malabar coast has a distinguishing feature in the form of ‘Kayals’ (backwaters). These backwaters are the shallow lagoons or the inlets of the sea and lie parallel to the coastline. These are used for fishing, inland navigation and are important tourist spots. The largest of these lagoons is the Vembanad lake. Kochi is situated on its opening into the sea.

The Eastern Coastal Plain

1. Extent: The Eastern Coastal Plains is a strip of coastal plain with a width of 100 – 130 km between the Bay of Bengal and the Eastern Ghats

2. Subdivisions: It can be divided into two parts:

- Northern Circar: The northern part between Mahanadi and Krishna rivers. Additionally, the coastal tract of Odisha is called the Utkal plains.

- Coromandel Coast (or Payan Ghat): The southern part between Krishna and Kaveri rivers.

3. A coastline of emergence: The eastern coastal plain is broader and is an example of an emergent coast.

4. Characteristic features:

- The eastern coastal plains are wider and drier resulting in shifting sand dunes on its plains.

- There are well-developed deltas here, formed by the rivers flowing eastward in to the Bay of Bengal. These include the deltas of the Mahanadi, the Godavari, the Krishna and the Kaveri.

- Because of its emergent nature, it has less number of ports and harbours. The continental shelf extends up to 500 km into the sea, which makes it difficult for the development of good ports and harbours.

- Chilika lake is an important feature along the eastern coast. It is the largest saltwater lake in India.

Significance of the Coastal Plains region:

- These plains are agriculturally very productive. The western coast grows specialized tropical crops while eastern coasts witnessed a green revolution in rice.

- The delta regions of eastern coastal plains have a good network of canals across the river tributaries.

- Coastal plains are a source of salt, monazite (used for nuclear power) and mineral oil and gas as well as centres of fisheries.

- Although lacking in adequate natural harbours, with a number of major and minor ports, coastal plains are centres of commerce and have attracted dense human settlements.

- The coastal regions of India are noted for tourist centres, fishing and salt making.

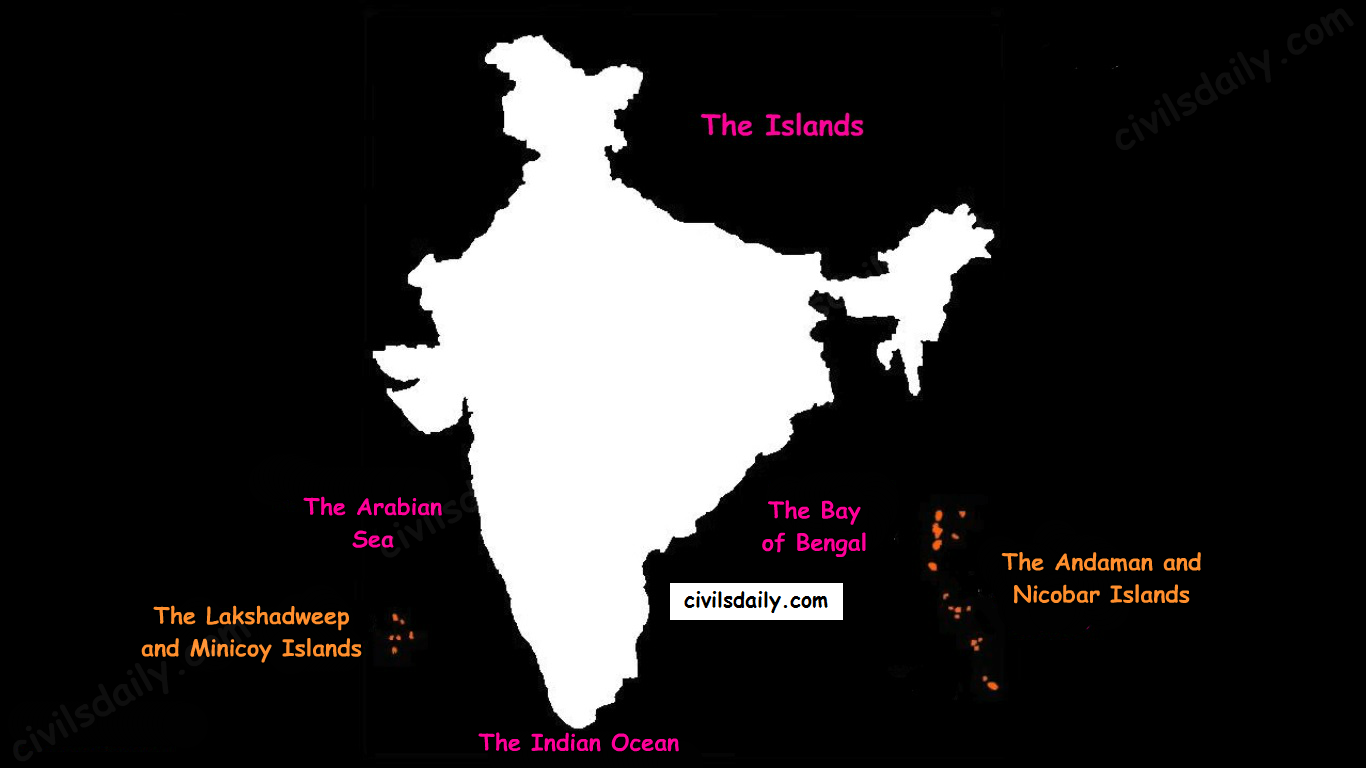

THE ISLANDS

There are two major island groups in India

- The island groups of Bay of Bengal: Andaman & Nicobar Islands

- The island groups of Arabian Sea: Lakshadweep and Minicoy Islands

Let’s take these up one by one:

Andaman & Nicobar Islands:

- Also called the emerald islands.

- Location and Extent:

- These are situated roughly between 6°N-14°N and 92°E -94°E.

- The most visible feature of the alignment of these islands is their narrow longitudinal extent.

- These islands extend from the Landfall Island in the north (in the Andamans) to the Indira Point (formerly known as Pygmalion Point and Parsons Point) in the south (In the Great Nicobar).

- Origin: The Andaman and Nicobar islands have a geological affinity with the tertiary formation of the Himalayas, and form a part of its southern loop continuing southward from the Arakan Yoma.

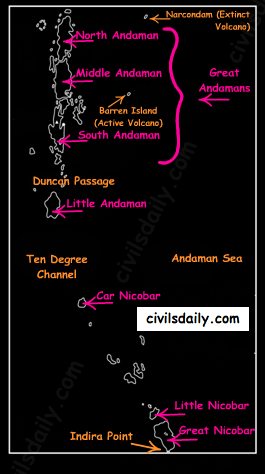

- The entire group of islands is divided into two broad categories:

- The Andaman in the north, and

- The Nicobar in the south.

They are separated by a water body which is called the Ten-degree channel.

- The Andaman islands are further divided into:

- Great Andamans

- North Andaman

- Middle Andaman

- South Andaman

- Little Andaman

- Great Andamans

Little Andaman is separated from the Great Andamans by the Duncan Passage.

- Chief Characteristics:

- These are actually a continuation of Arakan Yoma mountain range of Myanmar and are therefore characterized by hill ranges and valleys along with the development of some coral islands.

- Some smaller islands are volcanic in origin e.g. the Barren island and the Narcondam Island. Narcondam is supposed to be a dormant volcano but Barren perhaps is still active.

- These islands make an arcuate curve, convex to the west.

- These islands are formed of granitic rocks.

- The coastal line has some coral deposits and beautiful beaches.

- These islands receive convectional rainfall and have an equatorial type of vegetation.

- These islands have a warm tropical climate all year round with two monsoons.

- The Saddle peak (North Andaman – 738 m) is the highest peak of these islands.

- The Great Nicobar is the largest island in the Nicobar group and is the southernmost island. It is just 147 km away from the Sumatra island of Indonesia.

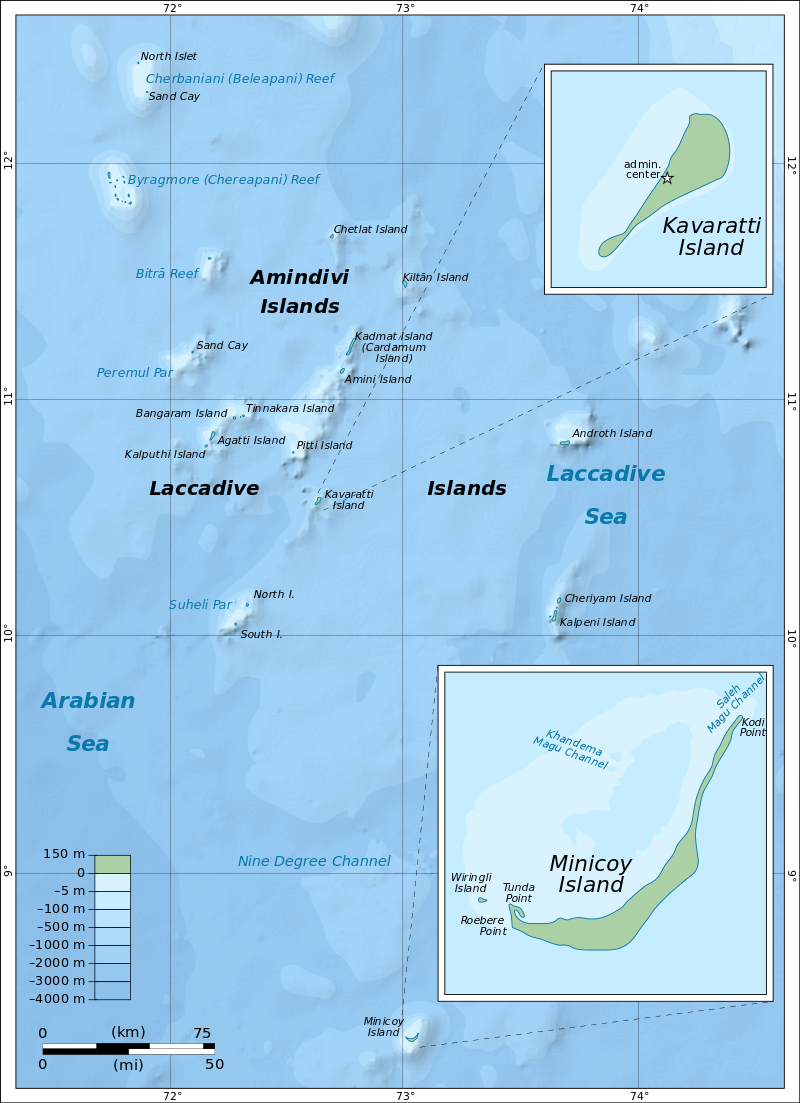

Lakshadweep Islands:

- These islands were earlier (before 1st November 1973) known as Laccadive, Minicoy and Amindivi Islands.

- Location:

- These are scattered in the Arabian Sea between 8°N-12°N and 71°E -74°E longitude.

- These islands are located at a distance of 280 km-480 km off the Kerala coast.

- Origin: The entire island group is built of coral deposits.

- Important islands:

- Amindivi and Cannanore islands in the north.

- Minicoy (lies to the south of the nine-degree channel) is the largest island with an area of 453 sq. km.

- Chief Characteristics:

- These consist of approximately 36 islands of which 11 are inhabited.

- These islands, in general, have a north-south orientation (only Androth has an East-West orientation.

- These islands are never more than 5 metres above sea level.

- These islands have calcium-rich soils- organic limestones and scattered vegetation of palm species.

- One typical feature of these islands is the formation of the crescentic reef in the east and a lagoon in the west.

- Their eastern seaboard is steeper.

- The Islands of this archipelago have storm beaches consisting of unconsolidated pebbles, shingles, cobbles and boulders on the eastern seaboard.

- The islands form the smallest Union Territory of India.

Other than the above mentioned two major groups, the important islands are:

- Majauli: in Assam. It is:

- The world’s largest freshwater (Brahmaputra river) island.

- India’s first island district

- Salsette: India’s most populous island. Mumbai city is located on this island.

- Sriharikota: A barrier island. On this island is located the satellite launching station of ISRO.

- Aliabet: India’s first off-shore oil well site (Gujarat); about 45 km from Bhavnagar, it is in the Gulf of Khambat.

- New Moore Island: in the Ganga delta. It is also known as Purbasha island. It is an island in the Sunderban deltaic region and it was a bone of contention between India and Bangladesh. In 2010, it was reported to have been completely submerged by the rising seawater due to Global warming.

- Pamban Island: lies between India and Sri Lanka.

- Abdul Kalam Island: The Wheeler Island near the Odisha coast was renamed as Abdul Kalam island in 2015. It is a missile launching station in the Bay of Bengal. The first successful land-to-land test of the Prithvi Missile was conducted from the mainland and it landed on the then uninhabited ‘Wheeler Island’ on November 30, 1993.